Renzo Piano architecture criticism, American Architects, US President Biden Building News

Renzo Piano, architectural criticism and global pandemic

Historic US Election Review of Architectural Aspects: Architectural Column by Joel Solkoff, PA, USA

Jan 8, 2021

US Architecture under President Biden Part IV

Joel Solkoff’s Column Vol. VII, Number 1

Auditorium by Renzo Piano, Morgan Museum and Library, New York City, New York:

photograph published by permission of the Morgan

Eight years ago, visiting the auditorium of Renzo Piano’s extension and renovation of the Morgan Library & Museum marked my transition from simply being a disability rights advocate to becoming an architecture critic as well. Indeed, as will become apparent, I was following in the footsteps of New Yorker critic Lewis Mumford who introduced Patrick Geddes’ urban planning teachings to US readers—principles Piano’s Morgan exemplifies.

The US is in the midst of a national crisis where the pandemic rages out of control— 320,000 of our people are dead— and the current occupant of the White House has failed to provide the leadership required. The architecture, engineering, and construction community (AEC) have the ability to build the millions of units President Elect Biden’s plans will require.

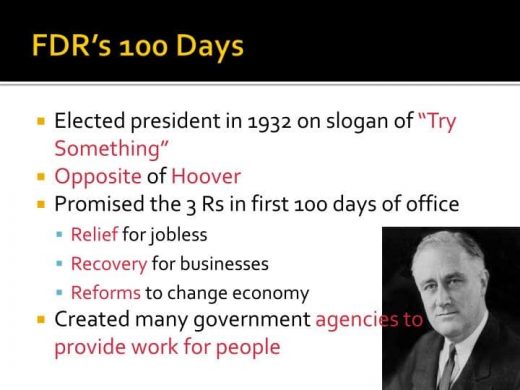

Architects and AEC community members generally would best prepare for Biden’s first 100 days— the metric President Franklin D. Roosevelt established in 1933 to deal with the Great Depression. Biden’s first 100 days will establish Administration plans, not only for building of housing, but for building cities to help control the pandemic. Perhaps, the lessons I learned from my intense focus on Piano’s Morgan may prove helpful.

FDR’s first 100 days as US president:

screenshot by Joel Solkoff

“A building should not stand out. It should fit in.”

Lewis Mumford, author of The Myth of the Machine

“The dresses I prefer,” said fashion designer Pierre Cardin, “are those I invent for a life that does not yet exist.”

View of the Manhattan skyline from the Queens, New York Regal Heights Nursing Home and Physical Rehabilitation Center where I am writing this column:

photo by Joel Solkoff

####

DATELINE – Wednesday, January 6 2021. Increasingly complicated has become my flight from rural Lycoming County. (where I have lived for the past two years) to New York City, where by comparison grown ups (albeit not perfect) appear to be in charge and hospital beds are available.

After I arrived at Penn Station on the evening of December 10th, I lost my luggage. The absence of disability signs to the wheel chair accessible elevator made me unable to exit the station underground for 40 minutes.

The following morning I arrived early at the offices of Dr. Paul Russo, the surgeon who eight years earlier had saved my life by removing a cancerous tumor that had surrounded my right kidney. Then, Dr. Russo put my kidney back together. A variety of serious problems neglected by rural America’s primitive health care system kept me at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for nine days. Currently, I am living at a nursing home and physical rehabilitation center in the NYC Borough of Queens where I await surgery to remove a tumor over my left kidney.

The challenges for controlling the global pandemic require that the most vulnerable in society–the elderly, the poor, the incarerated, farmworkers and the homeless– obtain safe housing. It is a challenge that reminds of dewy-eyed optimists like the main character in Miss Congeniality–embedded here in accordance with YouTube’s licensing agreement–seem the object of ridicule.

How I became an architecture critic with a disability focus

Ten years ago, when I was writing for HME (Home Medical Equipment) News and using virtual reality to design residences for the physically disabled, Adrian Welch, co-founder of e-architect.com, asked me to write about disability rights issues as they relate to architecture. As a paraplegic, unable to walk for the past 26 years, I have something to say about the built environment that can either gain me entrance to the world or exclude me.

Two years later I visited the Morgan Museum and Library a short distance from Grand Central Station. I had the good fortune of being given a tour of the Morgan by Frank Prial Jr., whose firm Beyer Blinder Bell designed the renovation of Ellis Island where my father Isadore first saw the United States as a refugee from deadly anti-Semitism in the Ukraine.

Prial—whose work renovating Grand Central Station was praised by the influential architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable—served as the Morgan’s architect of record because Piano did not have an office in New York State and could not sign off on his own work. Essential to Piano’s design goals was restoration of the original library. The 19th and early 20th Century robber baron J. P. Morgan had established. his library as explicitly closed to the public.

The 1906 McKim Meade and White structure housed Morgan’s personal collection of manuscripts, paintings and sculpture Morgan had stolen, bought and confiscated de facto but legally from the rest of the world, This year celebrating its fifteenth anniversary, Piano’s Morgan makes accessible to the public and especially the disabled one of the great artistic treasures of the world. Piano’s auditorium is a good example of disability access. The auditorium plays on instruments of the period Mozart et al. from the original score. Thus, the blind are given the ability to appreciate the treasure the Morgan contains.

One hundred fifteen years ago, the architecture firm of McKim Meade and White completed this personal library for JPMorgan. Morgan made his fortune as a financier for the Pittsburg, Pennsylvania firm US Steel ( just to show you just how significant is and was Pennsylvania to the economy and politics of the US):

photo in the public domain

Morgan was a master of the corruption widely prevalent at the time. When he grew tired of smuggling art past customs, historians remind, Morgan caused Congress to change the law to make acquisitions legal. Here is a Tom Nast cartoon from the Robber Barron era.

”The Magnet,” 1911 Punch Magazine cartoon: the magnet of Morgan’s fortune pulls the world’s art treasures to New York:

drawing published courtesy of the Morgan Library, NY, USA

How Renzo Piano obtained his first New York City Commission

Renzo Piano’s first New York commission arrived at Piano’s Building Workshop office in Genoa, Italy with the hasty arrival of J.P. Morgan Director Paul Spencer Bayard. Bayard pleaded with Piano for the second time to accept the Morgan commission. Bayard was in a difficult situation. The Morgan Board of Directions had authorized an architectural commission. Major New York firms had competed.

Piano had been asked to compete but he refused saying that he does not submit to competitions anymore. Then the Board refused to accept any of the plans the New York architects had presented. After considerable pleading on Bayard’s part, Piano agreed to fly to New York and look the site over.

Piano’s theme for the Morgan

Renzo Piano had never been to the Morgan Library. This is a view of the Renzo Piano’s entrance to the museum extension of the Morgan’:

photo by Anthony Troncale provided by permission of the Morgan Library and Museum

Piano later explained that as soon as he started drawing while still on the plane he realized he had accepted the project because the act of drawing meant that he was inspired and thus engaged.

After visiting the Morgan, I returned to my home in Central Pennsylvania where I did a series of video interviews with the principals who helped make the Morgan. Here is the first of two interviews with Georgio Bianci at Piano’s offices in Paris. A friend suggested I delete this video because of atmospheric noise. In retrospect, Bianci told me that Piano frequently designed at that location oblivious to the noise. Imagine that degree of concentration.

The first source for Piano’s inspiration was the surrealist novel The Infinite Libraryby Jorge Luis Borges. Piano explained to interviewer Cynthia Davidson, a member of the editorial board of the MIT Press series Writing Architecture:

“The infinite library is a great concept. It is a library made of infinite–not infinite—because infinite is a concept that ishumano, so it isalmostinfinite. Each room is a hexagon, and they touch each other and they go this way and that way, that way and that way and that way. So you are where you are where you were before in some way, in that mold where you see down and up. I immediately loved that idea when I came here.

“Manhattan is made of schist, and if you are lucky enough not to have a river under your foot, if you cut like a knife into it you have the best place to hold and conserve a secret or a treasure against time, weather, vandals, and all that.”

Aerial view: J.P. Morgan Library and Museum construction site during demolition:

photographer Moreno Maggi. Copyright © 2003 Renzo Piano Building Workshop

Conserving a treasure became one of the two co-equal themes of Piano’s master plan. Preserving the character of the neighborhood was the other. Above is the construction Piano directed applying the Borges theme to focus on the Morgan’s actual buried art treasure.

The Morgan asked Piano to implement: “state-of-the-art collection center.”Art collection center means a very large safe. Piano designed the sophisticated safe which holds the Morgan’s artistic treasures. He refers to the safe as a vault. Vaultrepeated over and over became the word Piano used most frequently to describe his creative concept. Piano architectural plan focuses on the Vault.

Here is a plot summary ofThe Infinite Libraryfrom Wikipedia: “Borges’s narrator describes how his universe consists of an enormous expanse of interlocking hexagonal rooms, each of which contains the bare necessities for human survival—and four walls of bookshelves. Though the order and content of the books is random and apparently completely meaningless, the inhabitants believe that the books contain every possible ordering of just a few basic characters….

“Though the majority of the books in this universe are pure gibberish, the library also must contain, somewhere, every coherent book ever written, or that might ever be written, and every possible permutation or slightly erroneous version of every one of those books. The narrator notes that the library must contain all useful information, including predictions of the future, biographies of any person, and translations of every book in all languages. Conversely, for many of the texts some language could be devised that would make it readable with any of a vast number of different contents.”

In his prime, Morgan was the wealthiest man in the United States which he remained until the day he died. Morgan spent over half his wealth on his collection. This is how Morgan’s management describes the collection:

“Pierpont Morgan’s immense holdings ranged from Egyptian art to Renaissance paintings to Chinese porcelains. For his library, Morgan acquired illuminated, literary, and historical manuscripts, early printed books, and old master drawings and prints. To this core collection, he added the earliest evidence of writing as manifested in ancient seals, tablets, and papyrus fragments from Egypt and the Near East. Morgan also collected manuscripts and printed materials significant to American history.”

Piano’s second Morgan theme

The second novelist who influenced Piano’s design of the Morgan was Umberto Eco. Eco is widely known as the author of Name of the Rose. Ecco wrote: “Books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told.” Piano and Ecco are friends. Piano told Cynthia Davidson about the advice he received from Eco:

“Before leaving [to accept the Morgan commission], I called my friend Umberto Eco; because a long time ago, he was telling me about this funny place in the middle of Manhattan where he found a beautiful place that he was passionate about—the Morgan. …So I called him because I remembered that one day we spent an evening in a nice little restaurant in Genoa talking about this idea of exploring, going underground to look for things….So I called him to say that I was talking with the Morgan about a project. ‘Oh, that’s great, fantastic,’ he said. ‘Don’t spoil that place. It’s a great thing. Then we started to talk about this idea of the safe, of the treasure. And he said, ‘You remember that piece from Borges? Read it again.’ Then I read it again. It’s beautiful.”

Piano’s seamless complex combines the old and the new. The Madison Avenue entrance leads to a spacious Atrium. From there the wheelchair lift took me on a five-foot ride straight up to the 1906 McKim Mead and White library:

photo by Kathy Forer

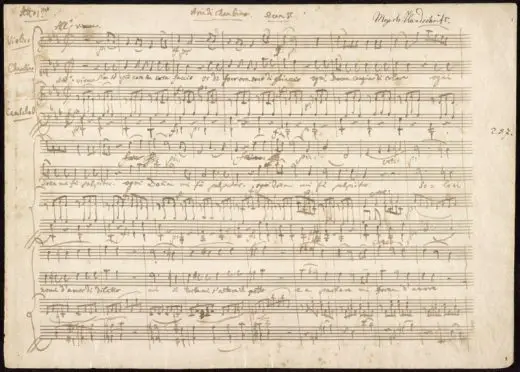

There, in the old library, made vastly more pleasurable by enhanced lighting, was the following manuscript Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote in 1786, complete with a curiously endearing smudge mark. In the movie Amadeus, Salieri talks about Mozart’s first drafts being perfect as if dictated by God:

photo by Anthony Troncale provided by permission of the Morgan Library and Museum

Eight years ago, I visited the Morgan while in New York to prepare for kidney cancer surgery. Mozart’s music helped me get through the experience. For each of us, there is something that makes it possible to transcend—to endure suffering or be lifted from the mundane. For me, on that day as I feared death, seeing Mozart’s handwritten score to the Cherubino’s aria from The Marriage of Figaro provided me with tranquility (a form of therapy if you prefer).

My 2013 trip to the Morgan was my first since I had visited the collection in 1971 when I worked nearby as a writer of educational materials. I frequently snuck out of the office and the demands to rewrite and rewrite again, to visit the library and gaze at the illuminated manuscripts. I have the experience of having seen the Morgan before Piano completed his work in 2006. I remember when I was able to walk. After Piano, physical access was not an issue I paid any attention to at all.

Renzo Piano’s reaction to his own work

“’It’s a miracle, I’m telling you,’ claimed Renzo Piano, ‘nothing less than a miracle,’” writes Brian Regan, co-author of the lavishly illustrated book The Making of the Morgan, From Charles McKim to Renzo Piano.

Regan continues, “We had walked, in early 2005, through the future Madison Avenue entrance and into the fully formed, but not entirely enclosed, central court.

“‘Brian, think about it: Only a few years ago these were thoughts and plans, and now they’re becoming real. How can that not be a miracle?’ In wonder, he added, ‘Ever since I was a boy, I thought a building site was a miracle. I’ll die thinking that.’”

Suggestions for Rep. Marcia Fudge on how to build for the future at HUD incorporating lessons learned from Piano’s Morgan

We architecture critics have each in our own minds a model for how to design appropriately. Clearly my model is Renzo Piano’s Morgan Library and Museum. The job ahead for Secretarial nominee Fudge is to obtain quickly the best available architects and other members of the AEC community. This will require a selection process which includes:

# the best talent available globally disregarding Made in America notions as far too limiting

# using a more focused selection process than can be obtained through than standard competition and rating systems HUD currently employees

# reliance on the ability of the architect to develop and execute a theme specific to the project at hand

# require accessibility for those with physical disabilities in keeping with universal design principles

One traditional mechanism for designing and solving major policy issues is a White House Conference. I suspect Biden will be establishing White House Conferences for housing as well as feeding the hungry, universal health care, etc.

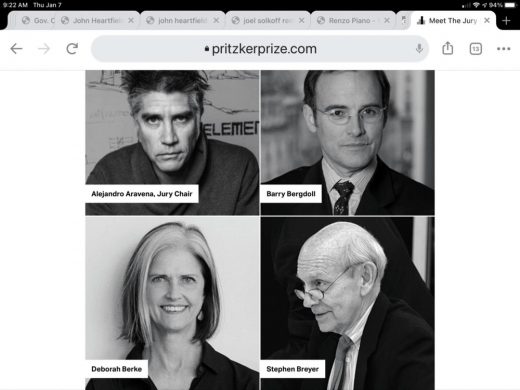

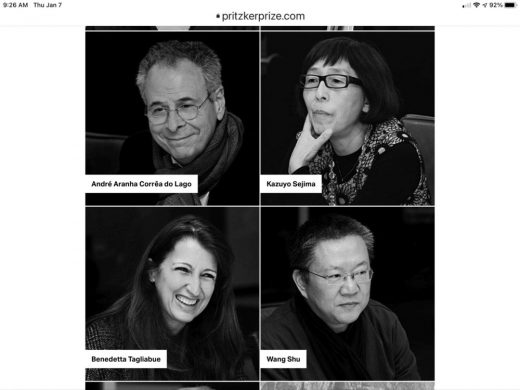

My initial suggestions is that Secretary Fudge request the jurors of the Pritzker Prize assist her in preparing to build not only housing units but cities to help control the pandemic. The current Pritzker jurors are:

Martha Thorne, Executive Director:

Manuela Lucá-Dazio, Advisor:

photos courtesy The Pritzker Prize Meet the jurors. For detailed biographical information see: https://www.pritzkerprize.com/jury

Meanwhile, the results of yesterday’s election in Georgia will mean that Democrats will control the US senate paving the way for increased expenditures for housing for the poor and vulnerable.

My editors beckon: “All right, stop writing, Joel.”

Isabelle Lomholt and Adrian Welch, Editors at e-architect.

Joel Solkoff, New York City, New York, USA

Please feel free to phone me at US 570-772-4909 or send an e-mail [email protected]

Copyright © 2021 by Joel Solkoff. All rights reserved.

Joel’s recent articles on e-architect

Dec 29, 2020

Architects: Keep Georgia on your mind

Dec 24, 2020

All Architects Must Be Covid-19 Architects

Nov 12, 2020

Architecture under the Biden Presidency

Architecture Columns

Architecture Columns – chronological list

Special Wooden Floors for Renzo Piano’s Whitney in New York

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, Queens Library

Renzo Piano’s Whitney Neighborhood

Disability-Access Architecture

US Architecture

Joel Solkoff’s Column Vol. IV, Number 2

Joel Solkoff’s Column Vol. IV, Number 1

Comments / photos for the Renzo Piano, architectural criticism and the pandemic – page welcome