Prison architecture will arrive after more research, USA Architectural Design, American Building News

Design matters: We Who Are About To Die Salute You

July 15, 2022

Joel Solkoff (1947 – 2022)

Sadly Joel Solkoff passed away on May 3, 2022 in his local Williamsport hospital, Pennsylvania, USA.

He was passionate about architecture, especially disability rights and affordable housing.

Joel Solkoff was a thinker, and for sure we need more of those in this world.

Read more about him here:

December 5, 2021

Prison architecture will arrive after more research: Architectural Column by Joel Solkoff, PA, USA

++++

Joel Solkoff’s Column Vol. VII, Number 6

![]()

screen shot by Joel Solkoff of a virtual reality model showing me as an avatar

Rural Williamsport, Pennsylvania, population 28,562 {By contrast, New York City’s population is 8.4 million.} Distance between them 192 immeasurable miles.

768,619 Covid-19 deaths in the US

— Center for Disease Control as of November 13, 2021

Extremism in defense of liberty is no vice.

— Barry Goldwater

We are going to have to live with Covid. We cannot eliminate it. We have to learn how to control it.

— Dr. Anthony Fauci CBS Face the Nation, November 28, 2021

Fear of death

The necessity for architects to design appropriately

On October 12th, I “celebrated” my 74th birthday sitting on my battery powered wheel chair waiting for days in a very cold emergency room at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania.The hospital, a 45 minute drive south from my home in Williamsport, is also here in the Rust Belt of the economically ravaged center of my politically powerful US state. I was in Danville rather than my primary home hospital because Danville has the only hospital within driving distance where all workers are vaccinated against the Corona virus.

I had disguised my internal panic with typical macho behavior, but the fear prevailed that unless I received prompt medical attention I would die. Specifically, I worried about my morning’s dangerously high 214 systolic blood pressure.

self-portrait photo : Joel Solkoff

My week long hospitalization which followed was the third time since December that I was hospitalized. On each occasion, I regretted my being a critic; rather than an architect capable of fixing the faulty design of medical facilities where death seemed ever present. It is not currently possible to be hospitalized in the United States without fear of Corona virus death predominating regardless of the reason for seeking medical attention. Clearly, the pandemic is especially effective at killing elderly physically vulnerable people like me.

I am a four time survivor of cancer; I have a heart condition complete with a pacemaker that hourly keeps me alive. I am a paraplegic and a distressingly large number of my contemporary friends have died or been institutionalized. In the past year or so, my attempts at sleep are all too often haunted by the fear I might not wake up.

Conversely, I have strong attachments to the world of the living because I have four grandchildren, have lived an exciting life which I savor in detail and because I have my work. Being an architectural critic specializing in disability consciousness takes on a bifurcated quality as I am a hospital patient and hospital reformer both at the same time. On the one hand there is the fear which I can often suppress as I analyze the absence of hospital windows, adequate toilet and shower facilities and understanding that because I cannot walk I must be incapable of independent behavior.

In 2021 I redesign hospitals in my mind and now for you because they need to be redesigned especially as my country faces a global pandemic we have yet to tame.

Evil architecture critic with cigarette holder plotting with corrupt architect 0 The Fountainhead, 1949 film:

Screen shot by Joel Solkoff

My second hospital

UPMC Medical Center—Williamsport

My hometown Williamsport PA hospitalization in July was accidental and reluctant. This was in sharp contrast to my Danville and New York City hospitalizations which were intensely sought. My primary care physician had urged me to continue taking medication that had once been beneficial. However, since I had lost 80 pounds in a short period of time, a small quantity had proven toxic and I went into a catatonic state. Frankie Rasole, my e-architect assistant editor and dear friend, put me in an ambulance, saving my life. Had I been conscious, I would have avoided that hospital because of its failure to insist on Covid vaccinations for all its workers.

In the process of loading me into the ambulance, Frankie called my two daughters Joanna, and Amelia, Amelia, living with her husband and my infant grandson on a Marine base in southern North Carolina promptly drove 15 hours to be with me. Joanna, based in a suburb of Washington DC scooped up her husband and my three grandchildren— age 5, 3, and 1–to drive 11 hours to be with me.

This outpouring of love demonstrated this critical problem as it relates to medical facilities expressed by my favorite architectural critic Lewis Mumford (1895-1990): “A building should not stand out. It should fit in.” Here in pandemic USA increasingly hospitals are isolated not fitting into the needs of its patients and community. This is especially the case in once prosperous, once well-populated communities like Williamsport county seat of Lycoming, one of the largest, least populated counties in Pennsylvania.

Williamsport does not have airline passenger nor train passenger service. Had my daughters wanted to be with me, their public transportation options would have been limited to busses— not an easy way to travel. Nor, indeed in this— as so many of our politicians like to express it—“the richest, most powerful country in the world” our roads are filled with potholes and many of our bridges are in poor repair.

Notice far right the handle bars of my battery powered wheel chair. As my otherwise excellent nurses pointed out frequently, it was unusual to have a disabled patient with the “ independence” to use a scooter go to the bathroom by him or her self:

photo : Joel Solkoff

The UPMC acronym for my UPMC—Williamsport Medical Center refers to University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Pittsburgh is 200 miles west of Williamsport. Philadelphia is 180 miles east. Here in the middle of the state, we are dominated by forces— money, political power, media attention—beyond our control. The consequence is a stubborn resistance reflected in the reality that in the midst of a dangerous pandemic, our local ( Pittsburgh controlled ) hospital had the majority of.its workers openly defying Covid immunization even though the vaccine now is readily available.

Welcome to my part of the Rust Belt. From the perspective of the Coronavirus, Lycoming County where I live is one of the of the most dangerous places in the United States. Lycoming County’s vaccination rate is 45 percent comparable to Alabama, the state with the lowest vaccination rate in the country. One political observer said about Pennsylvania, “There is Philadelphia to the east, Pittsburgh to the west and Alabama in the middle.” I live in and was hospitalized in the local equivalent of Alabama where life expectancy is lower than that of my country’s coastal states. The poor quality of health care here in Lycoming County can be accurately measured by examining the infant mortality rate.

Nationally, the US infant mortality rate is 5.9 infant deaths for each one thousand live births— one of the worst rates in the developed world. By comparison, the infant mortality rate in Spain is half that. Here in Lycoming County, PA, infant deaths consistently fail to achieve local public health goals and here the infant death rate is the highest in the developed world.

Time out: “Born in the USA”

Born in a dead man’s town

The first kick I took was when I hit the ground

You end up like a dog that’s been beat too much

‘Til you spend half your life just coverin’ up

Born in the U.S.A

I was born in the U.S.A

I was born in the U.S.A

Lyrics courtesy Apple Music

My third hospital

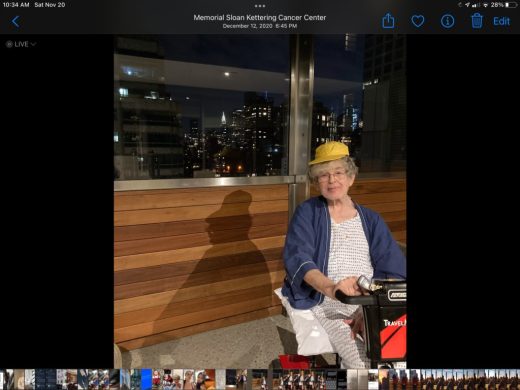

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center—New York City

Shortly after I arrived at Sloan Kettering, I was invited to celebrate the joyous Jewish holiday of Chanukah on this glorious balcony— the art deco Chrysler building above my right shoulder. Unfortunately, during my long stay, my hospital experience was confined to viewing the outside world from my sick room:

photo courtesy of the chaplain’s office Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

In December 2020, I fled Lycoming County terrified by the threat Covid 19 posed as nursing homes filled with corpses, I fled to New York City. Perhaps, in retrospect, my instinct to return to the city of my birth was not rational, but a fight or fight response. Perhaps. It was was it was. It was a multi-week plan to return to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan on York Avenue between East 67th and 68th Streets.

This was the view from my room:

photo : Joel Solkoff

Eight years earlier, upon receiving the diagnosis of kidney cancer, my local physician had urged me to go quickly to Sloan Kettering to save my life. There— seeminginly miraculously— Surgeon Paul Russo removed the cancerous tumor choking my right kidney and repaired the kidney.As a result I was able to give my two daughters away in marriage, hold my grandchildren and become— thanks to Renzo Piano— a real life architecture critic

How I became an architecture critic

My evolution into becoming an architecture critic had its origins in the preparations and circumstances surrounding my kidney cancer hospitalization,. As a compulsory frequenter of medical facilities since I first was diagnosed with cancer in 1976 at age 28, I had automatically reacted to the 2013 threat on my life with work— glorious work. In this case, work meant frequent visits—as if I were a truant schoolboy escaping hideous medical tests— to my favorite museum: McKim Mead and White’s glorious Morgan Museum, a hop skip and a jump from Grand Central Station.

Consider the advantage into escaping here to this rotunda:

photograph courtesy of Morgan Museum, NY, USA

Then, ( I write of course), enter stage right there was Renzo Piano about whom a mayor of New York City later referred to as a super hero. Piano’s remodeling of the Morgan Museum and Library turned me into a real architecture critic. Here is this photo of Italian architect Renzo Piano’s New York masterwork.

photo courtesy of Morgan Museum, NY, USA

My initial value to the architectural community stemmed from my perspective as one now confined to a wheel chair for the past 25 years. Ten years ago when my editor Adrian Welch asked me by way of LinkedIn to write for e-architect, I was not an architecture critic. Instead, I was a consultant helping with virtual reality design of housing for the disabled. Architecture was but one of a number of disciplines on which I commented as frequently as I was often asked.

Despite my on-going consistent complaints about the insensitivity of others to the disability perspective, the “insensitivity” involved is with scant exception not deliberate. Indeed, as I have traveled from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts of the United States, as I have done several times since I became mobility disabled, I am daily appreciative of the fact that people—regardless of political and religious views or locations— go out of their way to help me. I remember in Utah fixing the wheel chair lift underneath and on the rear of my automobile calling out to someone wearing shoes to hand me a pair of players and she did— sight unseen.

Years later, , I have come to understand the slogan of the international disability rights movement: “ Nothing about us without us.” Unless you are in a wheel chair, you cannot truly understand what it is like being in one. Often, the people about whom I complain the most are the ones who care the most and who try to help when helping is the last thing I want. There are days when I want to open doors by myself—when I complain about doors that are difficult to open because the built environment works best when I do not think about it.

photo courtesy of Morgan Museum, NY, USA

Without question it is Renzo Piano’s design of the marvelous Morgan Museum and Library in New York City that turned me from an occasional critic of architects into a full time architecture critic. Piano’s sensitivity to accessible design— when he appears not seem to be focusing on accessible design- can best be appreciated in the design of the Morgan’s auditorium.

J.P. Morgan’s collection included musical scores written by Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin. At the auditorium, musicians play Mozart reading from original manuscripts. This makes the collection accessible to the blind for the first time.

The problem with disability access at Sloan Kettering

In December I was not able to take a shower from my wheel chair:

photo : Joel Solkoff

Here I am in December appraising the shower in my hospital room from the prospective of my trusty Amigo Mobility Travel Scooter front left. Clearly, no shower awaits. Now, for the first time, I brought my critical judgment to my sick bed while previously I had escaped my hospital reality for better access elsewhere. Eight years earlier! the notion of criticizing this marvelous hospital that had saved my life would have been unthinkable. Eight years earlier, the shower at Sloan Kettering was not usable from a wheel chair. Instead, a marvelous hospital worker had carried me into the shower and fully dressed had held me up when we showered.

Perhaps, had I asked, one of the wonderful Sloan Kettering staff would have repeated the past, but I did not ask. Instead, I photographed as I had done back home in rural Pennsylvania and found that even here in one of the great hospitals of the world, the built environment of Sloan Kettering was also hostile to the disabled. No more did I find myself asserting, It is better in New York City than at home. Some things are better in New York; some better in Lycoming County.

++++

In December 2020, , when I arrived at Sloan Kettering, I showed up at the office of Dr.Paul Russo pleading with him to let me stay in the hospital until the newly announced Covid vaccine was available. Unlike back at home, where few seemed to take the pandemic seriously, everyone at my New York hospital took it seriously. Unlike home, where no one seemed to wear masks, in my New York hospital everyone wore masks all the time. Weeks earlier, I had tried to make an appointment with Dr. Russo but could not because my Williamsport doctor’s office failed to send my medical records despite persist attempts to get the office to do so. I had showed up at Dr.Russo’s office without an appointment and refused to leave until I saw him. My defiance had begun back in Williamsport where I had deposited myself at my doctor’s office and threatened to spend the night unless the staff informed my doctor that I would prefer being arrested rather than go without a test.

My defiance reminded me of my 1960s Civil Rights days where at age 14 I I had showed up as a freedom rider at a bus station restaurant in Athens, Georgia with two black ministers and refused to leave until being served a grilled cheese sandwich and Coke. The rules for non-violent demonstration were as clear then in Georgia as they became in Williamsport and New York. It was a spiritual issue. As long as I presumed to defy local law asserting God’s law and I was willing to go to jail if necessary, then I could proceed. Regarding the danger the pandemic posed , I believed then that my life was at stake. Internally, I repeated to myself the great Rabbi Hillel’s unanswerable rhetorical,question, “If I am not for myself, who is for me?”

What I said to Dr. Russo worked. I said, “There is no question that you saved my life. Under Jewish law, if someone saves a life, one is responsible for that life. But you are exempt because you are not Jewish,” I paused.Dr.Russo said, “I do not need to be Jewish to accept that.” Promptly, he sent me to another building for a battery of overdue kidney tests that could not be performed in Williamsport. When, blissfully the tests were negative, he took a look at me with concern and sent me to urgent care. There my systolic blood pressure was at the dangerously high 214 level and I was admitted to the hospital where I wanted to be.

After my blood pressure got under control, the vaccine had not yet arrived. I was offered the choice of going to a nursing home in the New York City borough of Queens where I was promised intense physical therapy which for me is the moral equivalent of a banana split.

I arrived at the nursing home by ambulance:

photo : Joel Solkoff

During two of my three hospitalizations, I rode an ambulance. On each occasion, the ambulance was inadequate for a disabled patient in need of a battery powered mobility device. The ambulance personnel assumed for no reason that my Amigo Travel Scooter would not fold up and fit. At New York and Danville, I refused to enter the ambulance unless the scooter went with me and in each case I prevailed.The alternative would have meant I could not take the scooter from bed to bathroom; instead being forced to use a bed pan.

A day after arriving at Regal Heights Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, I was diagnosed as testing positive for Covid. Despite the best efforts of Sloan Kettering I had caught the virus there. Asymptomatic, I was treated promptly and less than three weeks later received in February of this year both doses of the Pfizer vaccine which I am convinced saved my life.

Notice the joy of the nurse who administered the vaccine back when fewer than one percent of the US population was vaccinated.

“Today’s column, I wrote on June 6th, describes a one-day trip I took took on a battery-powered wheelchair on Tuesday February 16th from a nursing home in the New York City Borough of Queens where– the day before– I received the second dose of the Pfizer vacinne to a cab to Manhattan’s glorious new Moynihan Train Hall .

Then, after a lenthy train ride to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s capitol city, a one hour and 20 minute automobile ride to home. To Williamsport, my home.”

new-york/remembering-new-york-city-architecture-of-my-youth

Stay tuned for my next column Why Williamsport is special and sadly in danger of dying?

Please consider the following as a preview

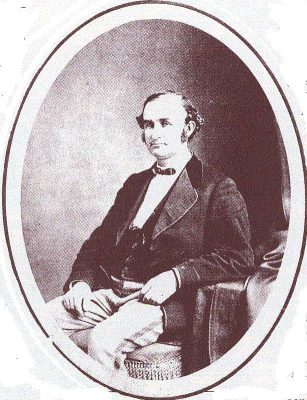

Peter Herdic, Williamsport, PA, USA:

photo in the public domain

Peter Herdic

Wikipedia excerpt: Peter Herdic moved to Williamsport in 1854, which was then a small village of 1,700 people surrounded by vast stands of virgin hemlock, white pine and various hardwoods. The lumber industry had existed in Lycoming County since the first Europeans arrived prior to the American Revolution, but it did not become the land-changing and eco-system altering industry until Peter Herdic and men like him arrived on the scene in the mid-19th century.

The lumber era began in force in 1846 when the Susquehanna Boom, a series of cribs for holding and storing floating logs on the West Branch Susquehanna River was built under the leadership of James Perkins. Herdic was able to use his business sense, leadership abilities, and according to some questionable business tactics to rapidly acquire wealth by buying and selling several tracts of timber and several sawmills. He used his gains to purchase several tracts of land in Williamsport, more sawmills, and eventually the Susquehanna Boom.

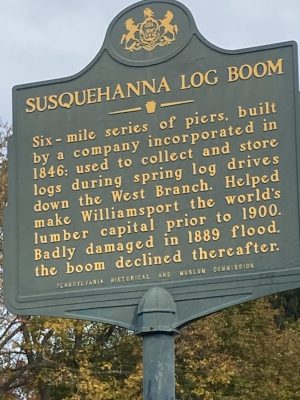

Plaque about the Susquehanna Boom, Lycoming County, Pennsylvania in the United States:

photo : Joel Solkoff

Peter Herdic and two business partners, Mahlon Fisher and John Reading, purchased the Susquehanna Boom and expanded it so that it could hold up to 300 million board feet (700 million m³) of lumber. At this time the most efficient sawmill in Williamsport could process only 100,000 board feet (200 m³) of lumber in a week.[3]

The sawmills at first could not possibly keep up with the vast amounts of lumber floating in the West Branch. The approximately 60 sawmills along the river between Lycoming and Loyalsock Creeks operated day and night on a year-round basis. Peter Herdic, his partners and many other businessmen in Williamsport, became fabulously wealthy. They made Williamsport, “The Lumber Capital of the World” with the highest number of millionaires per capita of any city in the United States.

Peter Herdic used his wealth to gain political power in Williamsport and Lycoming County, and led the drive to have Williamsport chartered as a city in 1866. He spent $20,000 to get elected mayor of Williamsport in 1869.

Local saloon keepers reported that Herdic would leave $10 and $20 bills among the bottles of their taverns for anybody that would vote for him in the election.

Plaque about Peter Herdic, Williamsport, PA, USA:

photo : Joel Solkoff

Prior to Herdic’s arrival, the Newberry section of Williamsport was known as Jaysburg and had vied with Williamsport to be the county seat of Lycoming County. Herdic saw to it that the rival community on the west bank of Lycoming Creek would no longer compete with Williamsport by leading the cause to annex the community to Williamsport.

Herdic had such influence that he was able to have the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad move their passenger station from the Pine Street area to his Herdic Hotel on West Fourth Street. Herdic was able to profit from this since the trains would now deposit their passengers at the door of his opulent hotel.

Peter Herdic, Williamsport’s 19th Century urban designer

A relevant photo gallery in honor of Peter Herdic, Williamsport’s 19th Century urban designer:

Trinity Episcopal Church designed by urban planner Peter Herdic, Williamsport, PA, completed 1875:

photo : The Rev. Kenneth Wagner-Pizza

Trinity Episcopal Church, Williamsport, PA, interior:

photo : Joel Solkoff

Williamsport has a beautiful historic district worthy of preservation as the pandemic raises questions of where and how to design cities. Design of cities has been a strong part of this column for years. Today, urban design at urban design is critical.

Copyright © 2021 by Joel Solkoff. All rights reserved.

My editors beckon: “All right, stop writing, Joel.”

One of the largest architectural sites in the world – contact isabelle(at)e-architect.com.

The e-architect resource has over 30,000 pages of architectural information + building news

#####

Joel Solkoff, US Editor, e-architect, USA Please feel free to phone me at US 570-772-4909 or send an e-mail [email protected] Copyright © 2021 by Joel Solkoff. All rights reserved.

Comments on this Design matters: We Who Are About To Die Salute You post are welcome

American Architectural Discussion

Joel’s recent articles on e-architect

Build a city of 100,000 in rural Central Pennsylvania

Moynihan Train Hall New York architecture of my youth

A new US capital city and my coronavirus experience

Architects: Keep Georgia on your mind

All Architects Must Be Covid-19 Architects

Architecture under the Biden Presidency

Architecture Columns

Architecture Columns – chronological list

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, Queens Library

Renzo Piano’s Whitney Neighborhood

Detroit Dying Special Report Disability-Access Architecture

US Architecture

Joel Solkoff’s Column Vol. IV, Number 2

Joel Solkoff’s Column Vol. IV, Number 1

Comments / photos for the We Who are About to Die Salute You – page welcome