Shelter Global Dencity Competition 2016 Winners, Slum Design Contest News

Shelter Global Dencity Competition 2016 Winners News

Architecture Contest – Improving Living Conditions for Slum Dwellers

19 Jul 2016

Dencity Competition 2016 Winners

Shelter Global Announces Winners of 2nd Annual Dencity Competition

Shelter Global has just announced the winners of its second annual Dencity Competition, highlighting innovative solutions that will improve living conditions for over 1 billion slum dwellers worldwide.

Shelter Global Dencity Competition Winners in 2016

After receiving over 350 registrations from 50 different countries at last year’s inaugural Dencity Competition, Shelter Global (an international architecture non-profit) decided to continue their competition on a yearly basis. The Dencity Competition was started as a way to foster new ideas on how to handle the growing density of unplanned cities. There are currently over 1 billion slum dwellers in the world and this number is expected to reach 2 billion by the year 2030. Now, more than ever, architects and planners need to play a central role in the development of substandard neighborhoods. Contestants were asked to consider how design can empower communities and allow for a self-sufficient future. The competition jury consisted of 8 renowned architects and urban planners.

First place was awarded to Jai Bhadgaonkar and Ketaki Tare from Mumbai.

Their project, Versova Koliwada, aims to address critical issues relevant to the design of the Koliwada community. They propose incorporating floatation devices that would positively impact the mangroves and coral in that area. The base of a floating island can be created by tying the bottles into plastic nets and attaching them to wooden boards. Jury member, Katie Crepeau, states that “the proposal has a deep understanding of the not only the local community but it’s wider connection to the city of Mumbai in social, economic and political contexts.”

Second place was awarded to Lauren Brosius, a recent graduate of Philadelphia University.

Her project, Incremental Alex, focuses on the Alexandra Township in Johannesburg which is one of the poorest urban areas in the country. Her proposal revolves around the idea of refocusing RPD funding toward improving the infrastructure rather than just building homes.

By providing residents with basic infrastructure it allows them a way out of the poverty cycle as well as brings growth and formality to a very informal situation. Jury member, Julia King believes the project was a “very good analysis of a deprived and peripheral neighborhood combined with a sound proposal for how to incrementally develop housing.”

Third place was awarded to the team of Amira Abdel-Rahman, Gabriel Muñoz Moreno, Santiago Serna Gonzalez from Harvard.

Their entry chooses to address the ventilation of slums. They focus on retrofitting existing slums and improving their thermal performance through a passively powered space conditioning system. Peter William’s from Archive Global notices that this project is “tackling one of the most pressing issues in informal settlements, offering a radical solution.”

Anyone interested in reading more about the 2016 Dencity Competition (including full project boards of winners and special mentions) can visit the website http://shelterglobal.org/competition.

Shelter Global would like to thank the jury for their work reviewing the numerous projects that were submitted to the 2016 Dencity Competition.

- Andrew Balster – Executive Director for Archeworks

- David Cole – Director of Building Trust International

- Geeta Mehta – Professor at Columbia University, co-founder of URBZ

- Julia King – Architect and Urban Researcher, Emerging Woman Architect of the Year

- Katie Crepeau – Former Editor-in-Chief for Impact Design Hub

- Michael Murphy – Founder of MASS Design Group

- Peter Williams – Founder of Archive Global

- Robert Elkins – Winner of 2015 Dencity Competition, co-founder of OC Workshop

Shelter Global Dencity Competition Winners in More Detail

Dencity Competition 2016 Winner – Mumbai: Versova Koliwada

DENCITY 2016: 1ST PLACE AWARD

Entry by: Jai Bhadgaonkar, Ketaki Tare

Introduction

Urban villages are the result of rapid urbanization. Natives can easily become engulfed into the urban fabric. One such example is Mumbai, India. Dating back 400 years, members of the Kul (Koli) tribe, who migrated from the mainland of Aparanta at beginning of Christian era, have survived this segregation. Mumbai is made up of 7 islands. The Kolis (Fisherfolk) were the first inhabitants to live on these islands. These fisher folk, known for their spirited fun-loving way of life, live in small settlements spread across Mumbai’s coastline. The ‘Versova Village’ is one such settlement of 27 existing villages today.

Our study includes analysis in the urban context, the governmental development programs and the historical and cultural facts affecting this settlement. Our study reveals that Mumbai’s urban villages, vaguely acknowledged under the Gaothan Act, are ensured cheaper cost of living, land prices and livelihood opportunities. This ultimately causes a surge in migrants, making the settlement grow denser. With over 5,000 inhabitants, it is now recognized as a slum by the government.

The settlement, in spite of a diverse caste system, has thrived with the help of various existing activity centers and ancillary industries. The open air gathering spaces that cater to vibrant cultural festivities has also helped this bonding to sustain. However, the deteriorating conditions are liable for the suppressed aspirations of these natives compelling them to look for opportunities outside of the settlement.

Versova Village is situated along a creek. The industrial effluents and solid waste (especially plastic debris) from the neighborhood pollute the 19 km long Oshiwara River before it concludes into the creek. Due to the nature of the water currents, the solid waste eventually settles on the coasts of the Koliwada. During monsoons, the coast witnesses heaps of plastic debris as high as 15ft. The small mangrove forest near the sea is thus; extremely polluted resulting in a loss of breeding in the mangroves. All of this is hazardous to both human and marine life.

The consequence of this extreme pollution has brought about an increase in the fish mortality, especially at the intersection of the creek with the Arabian Sea which was once a breeding space. All of these conditions have impacted the livelihood sustenance of this settlement. Depleting fish catch lies at the root of the predicament which further affects the economy, affecting various allied skilled occupations existing in the settlement, at the same time fueling ecological concerns.

The Concept

The proposed four phased intervention encompasses a number of critical issues relevant to the design of the Koliwada community. It addresses two major overarching issues: integration and sustainable development. It also intends to disperse the existing social boundaries among the natives and city dwellers. It also aims to build a connection between integrated governance, spatial integration and environmental sustainability since these fishing communities have an “unseen future” as far as livelihood is concerned.

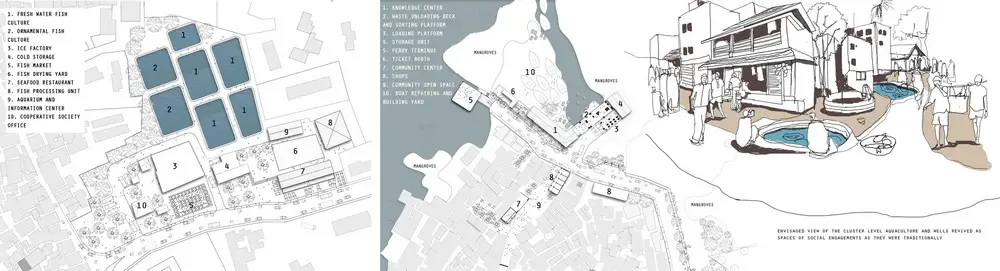

The first phase aims to commence a knowledge center with support of the established Versova Co- operative Society. The Versova Co-Operative Society is the primary reason why this settlement thrives in comparison to the 27 other villages. This knowledge center aims to insert new activities and services based on the logic of micro- intervention. This would cater to the needs of the infrastructure facility and enhance the skills of the natives (i.e boat builders, net weavers and fishermen). It would blend low-tech sustainability and provide newer applications of the unused waste, enhancing the allied ‘skills’ of the inhabitants that were previously not envisaged. While the implementation of these interventions starts at the micro level it envisions its impact globally as well.

The first step of this phase creates designated focal points for waste collection and segregation. One of the major pollutants responsible for the ecological degradation at various layers, including the coastal and mangrove degradation, is plastic debris. This debris sinks into the costal and marine environment causing habitat destruction and bio-invasion.

This particular fishing community has adapted modern techniques in spite of having only seven types of nets remaining in operation, amounting to three hundred nets total. This center would teach natives critical net weaving skills in order to build a duplicable water filtration system. New nets would then be used to make filter screens that would suspend 2 meters into the creek, anchored along the edge to ensure smooth movement of fish while focusing on waste collection. The plastic debris obtained from the comprehensive sorting of the waste is then used for newer creative applications. Part of this waste is also transported to Dharavi for recycling and reuse.

Plastic bottles are also used to make “poor man’s boats,” which are floats made of plastic gunny bags with three compartments, which are then filled with empty plastic bottles stitched to make a homogenous mass. Its design and the air in the empty bottles allow it to float. This can be further modified as per the purpose of its usability.

This proposed floatation device would positively impact the mangroves and coral. The base of a floating island (diameter of 18 meters) can be created by tying the bottles into plastic nets and attaching them to wooden boards. Among the various ancillary industries, the boat repair industry ensures the supply of worn out wooden members for this intervention.

This technology is also used to build inflatable tubes/rings used for the closed system aquaculture.

The above interventions would allow the participation of natives with their existing skill sets while encouraging team work. This would hopefully lead to the socio-economic and cultural permanence within the community. The evolution of the design would eventually stimulate employment and entrepreneurial opportunities expanding the existing ancillary industries and encourage the germination of other small scale industries.

The second phase aims to introduce closed system aquaculture in the creek as it is one of the most environmentally conscious methods of rearing aquatic species. This would assure more fish catch and strengthen the central element of sustenance at the socio-cultural and economic level.

Intensive and indiscriminate trawling in the coastal waters to meet the rising demand for shrimp has resulted in the exploitation of resources. Therefore, phase three aims at uplifting the economy to strengthen the fish market by introducing an inland fish culture where fresh water and ornamental fish breeding will be carried out. With India ranking second in the world for inland fish production, these wide ranges of interventions would uplift settlements, empowering all sects and classes that the village accommodates.

The final phase aims at setting up Fish Processing Industry. This expansion would enhance its reach to city levels establishing social engagement without social-economic bigotry. It would also preserve the cultural vibrancy of the settlement. This intervention includes setting up a restaurant, an aquarium and an information center. This would also reintroduce spaces designated for organizing city level workshops and even encourage the sales of local fish products (i.e. pickled fish) especially during the Versova Sea Food Festival hosted every year. This would also boost exports of these products to the city and eventually regional levels. Increased income, better purchasing power, education and awareness are even more affects that would result in the increased demand and value of added products. Setting up a fish processing industry will also attract investors and potential developers, ultimately fostering occupational mobility.

These interventions ensure a sense of belonging to inhabitants at the settlement scale. Our proposal also explores possible solutions for low cost building construction implementing the technique of earth bags with local materials. This building technique would be demonstrated at social engagement points across the neighborhood. This could then be used by residents for housing construction.

Conclusion

These proposed interventions can be envisioned as ripples in the sea. The central element spreading further with other punctual components can be viewed as a duplicable system for various settlements with similar issues. This system is not just an answer at the community level – it extends to form a regional socio-economic network. The merger of the social boundary between the city and the slum dwellers not only complements each other on their respective strengths, but also helps them in thriving together. Curbing waste in the settlement acts as a stepping stone that would ensure less addition of ‘gyres’ to the ocean. Entrenched in environmental consciousness, the core elements of this proposal end up contributing at a global level when scaled.

About the entrant

Jai Bhadgaonkar is an architect and urban designer based in Mumbai. He completed his bachelor’s degree in Architecture from L. S. Raheja College of Architecture, Mumbai in the year 2007. He has worked in the field of architecture with Sameer Rege and P. K. Das, in Mumbai from 2007 – 2009 after which he set up his own design firm, ‘Earthians’ in 2010. During the course of his practice, Jai developed a keen interest in the field of urban design. He pursued his masters in urban design at CEPT University, Ahmedabad. Since 2013, Jai has worked as an architect and urban designer at URBZ in Mumbai. He is currently trying to nurture his latest design firm, Bombay61. Recently, he has been working on projects based on place-making and incremental housing in economically deprived areas of Mumbai using his design skills to improve local conditions.

Ketaki Tare is an architect and an urban Designer practicing in Mumbai. She graduated from Sinhagad institute in Pune in 2008 and practiced under architect Narendra Dengle. Since then, she has been a professor at PVP institute of architecture. She completed her masters in urban design from CEPT university. Afterwards, she worked under Architect Sanjay Puri until 2014. She has worked for MESN and URBZ promoting sustainable design. Ketaki is the co-founder Bombay61 and has been working on design projects based in economically deprived areas of Mumbai. She is also teaching architecture and urban design in various architectural institutes in the city.

Dencity Competition 2016 2nd Place – Johannesburg: Incremental Alex

DENCITY 2016: SECOND PLACE AWARD

Entry by: Lauren Brosius

Introduction

By 2045, 80% of the world’s population is expected to be living in urban areas and currently 1 billion urban poor are residing in informal settlements. Alexandra Township (Alex) in Johannesburg, South Africa was established in 1912 for a white residential township, but it was far from the center of Johannesburg and was not a success. Prior to the 1913 Land Act, this was one of the few urban places black people were allowed to own land. Alexandra is located close to the wealthy areas of Sandton and Wyberg, while Alex is one of the poorest urban areas in the country. Home to a fluctuating population of 350,000 to 700,000 people in a 2 square mile area, Alex is characterized by the resident’s struggle for the right to remain in the city. Throughout the years there have been many removal schemes in place to remove the “black spots” from the city. By the 70’s there was not much formal housing, therefore people were forced to live in backyard shacks, pavements, river banks, and squatter camps.

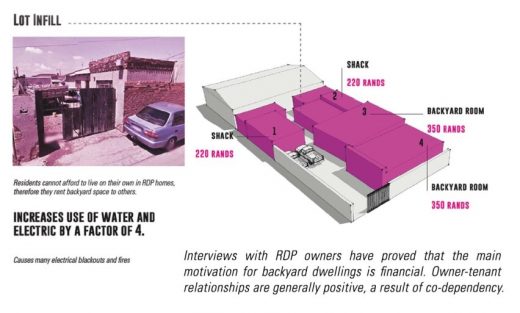

In 1994 the African Nation Congress took control and their main agenda has been to deal with the socioeconomic problems brought about by the apartheid. The current constitution states that “everyone has the right to have access to adequate housing” and the “state must take reasonable legislative and other measures within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realization of this right.” To reach this goal the ANC created the Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP) to build and allocate houses. Although the RDP on paper sounds like a positive impact to the people, it seems to have caused more harm than good. Roughly 43% of households in Gauteng have at least one person on a wait list for an RDP home and there is an ever growing backlog of 2.1 million people waiting for homes. The Reconstruction and Development system in Alexandra needs reform, strictly focusing efforts on building homes does not lift people from poverty. They are desperately in need to a more holistic approach to housing, infrastructure, and community relationships. The question that lies ahead is where are people living instead of their non-existent RDP homes?

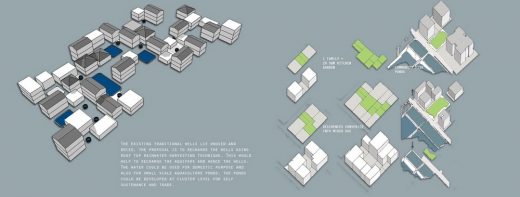

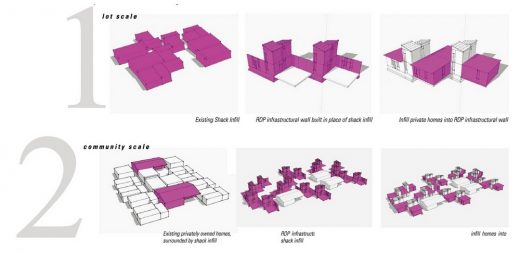

Research

Interviews with community members have shown that residents of Alex are living in backyard shacks of RDP houses, which has proven to be a very positive, co-dependent relationship. Too many of the owners, backyard dwellings are a very important source of income and for the tenants these accommodations offer improved living conditions and security. Backyard shacks paired with suitable infrastructure could be a solution to keep the density of the rest of Alexandra and diversify RDP housing. Currently the problem lies within the fact that RDP homes replace existing shacks at a much lower density and efficiency then what is necessary in Alexandra. The government of Johannesburg has already made recommendations for Alexandra to have a density of 75-200 dwellings per 100,000 square feet. These recommendations do not align with the current RDP model. They infill below 75 dwellings per 100,000 square feet and needs to be updated to reflect the city needs. Concurrently, large scale infrastructure in Alexandra has been unsuccessful and the shack infill only complicates the situation, there are many sewerage backups, electric blackouts and not enough water pressure or running water. A more effective government housing strategy focused on user participation, flexibility, and micro-grids may receiver greater user satisfaction, control infrastructure challenges, as well as urban density.

Only about 20% of the informal housing in Alexandra is recognized; the government is not looking at the informality between the formal housing. 85% of people living in Alexandra make less than 3,200 rand per month ($274), therefore contributing to not being able to afford their RDP homes and the expenses that result. Because much of this housing is informal, they do not have access to basic services. The average RDP home has a lot size of 80m2 and an average house size of 36m2 therefore the land is used very inefficiently and infilled with backyard shacks. These renters living in the backyard dwelling help the homeowner to pay for electric and water bills (84 – 200 rand per month or $5.8 -$14) as well as other expenses that come with living in a home rather than a shack. 51% of people living in shacks have access to trash removal, 5% have access to basic sanitation, 66% have access to basic running water, and 27% have access to electric in their dwellings. These numbers further establish that people do not only need a place to live in they need a new system to give them basic infrastructure. The goal is to create a more effective and community based public housing strategy which first provides basic infrastructure through a system of micro-grids, while maintaining density in Alexandra.

The Concept

Reallocation of the existing RDP funding is the first step in the process. Instead of using RDP funding to build houses for people, the money should be used to set up long lasting infrastructure systems for the people of Alexandra to promote formality. By providing residents with basic infrastructure it allows them a way out of the poverty cycle as well as brings growth and formality to a very informal situation. To address the issue of housing a new incremental methodology will be employed. A system of “wet blocks” and “dry walls” will construct the basis for new RPD dwellings in Alex. The module consists of four homes defined by three SIP panel walls with electric and one bathroom/kitchen block per home.

The SIP panel modular components are able to be used in different combinations to create varying lengths and patterns. Each home will be provided with a private bathroom/kitchen block, which houses and tub, toilet, sink, laundry sink, and solar hot water tank. The opposite side of the bathroom module will be a small kitchen with essential appliances. In this incremental housing scheme the rest of the house is left up to the owner who receives it. They are able to connect to the module with any construction type they can afford as well as expand or upgrade when necessary. On a larger community scale homes are arranged to allow for as much outdoor space as there is indoor space. Each resident is allotted and 8’ x 28’ garden space and between every 16 homes there is a large interior courtyard. This new system of housing infills at a density of 120 homes per 100,000 square feet, not displacing any existing shack infill.

Urban density is a problem that we need to plan for in the future because it is already happening. Our solutions need to be able to expand for future generations and keep up with expanding growth rates. Therefore if the infrastructure is up to par with the influx of people entering cities, we can build and expand on homes as necessary. To further develop the proposal, the next steps would be to develop a manual for people in these urban centers, such as Alexandra to explain how these panels go together and suggestions for how to connect to them. Detailed connections for brick, metal, wood, and more SIP panels are created and then given to every new owner. This will aid in the process of rebuilding homes after these new structures are built. The final step would be to organize a plan to ensure that housing densities do not rise above 75% and that public spaces are used for social activities and not more housing.

The intent is to understand growing urban centers and design an effective, yet personalized solution that addressed housing as well as infrastructure. The prototype that was developed based on the thesis achieved user participation, through residents building the remainder of their homes, with the materials that they wish to build it with. Flexibility is designed into the system using the SIP panels because they can be arranged in many different configurations. Each “wet block” creates its own micro-grid of bathrooms and kitchens that will be able to regulate supply and demand, therefore not causing overloads. This incremental housing solution for Alex prepares for the future by implementing a plan for infrastructure more so than building homes.

About the entrant

Lauren Brosius is a recent graduate of Philadelphia University and holds a Bachelors of Architecture and a Minor in Landscape Architecture. During her time at Philadelphia University, Lauren studied abroad in Copenhagen, Denmark and has traveled around the world extensively since then. She is currently an Intern Architect at EwingCole’s Philadelphia Office, on their education team, where she works primarily in schematic design and design development. Lauren is actively working towards her architecture registration by working on her IDP hours. Lauren excels when being challenged in the creative design process, where she possesses prominent visual skills. Lauren looks at every experience as a way to grow, to learn more about architecture and its effect on life and the world around us.

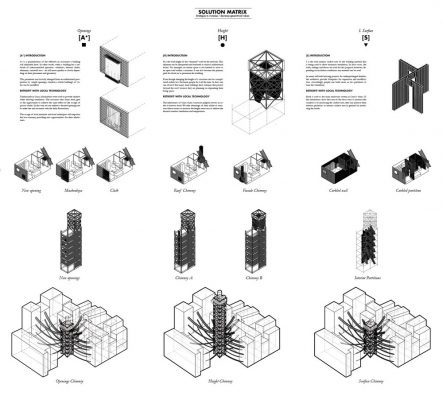

Dencity Competition 2016 3rd Place – Cairo: Allometric Sake

DENCITY 2016: THIRD PLACE AWARD

Entry by: Amira Abdel-Rahman, Gabriel Muñoz Moreno, Santiago Serna Gonzalez

Core Interest

The relentless growth of cities urges for solutions that relate to the improvement of levels of comfort in confined spaces. Slums, being directly affected by the lack of space, are an intriguing object of study. With constraints on cost and feasibility, we believe the population will greatly benefit from a passively powered space-conditioning system.

How? Software “Sake”

We have developed software that provides strategies that most affect natural ventilation by changing the following parameters:

A* (Openings): The value refers to the amount, geometry and distribution of openings that a building has to the exterior and interior network. These openings usually are windows, doors, chimneys, etc. The variation of this value will help to define the amount of fresh air coming into the building.

H (Height): This parameter refers to the height of a building. Hot air is driven to the upper part of a building due to its decrease in density, and vice versa when cold. This phenomenon creates differences in pressure, generating the opportunity to drive passive ventilation with the control of this parameter.

S (Interior surface): The interior surface area mostly affects to the amount of energy that a material can absorb and release. Changing this parameter will allow us to control the temperature of an interior according to current adaptive comfort models.

These values depend on a climate analysis that our software “SAKE” performs. With the climate data extracted from a specific location, we can provide a desired ventilation rate (Fn) to determine the amount of fresh air that a building has. If this rate is high, the ventilation will be high, if this rate is low, the ventilation will be low.

All these parameters are part of relationships that our program “SAKE” uses. Thanks to vector data collected from GIS like “Open Street Maps” or “Google maps 3D viewer”, we can analyze existing buildings and provide retrofit or new design strategies.

Our efforts will be focused toward the following goals:

Definition of comfort zones (ASHRAE): This will set goals in terms of finding ideal living conditions according to the location of study. If climate conditions are too extreme for the implementation of Athermal resonator strategy, we will suggest ways to improve living quality during other seasons.

Extrapolate the analysis: Our ultimate goal is to design a simple tool that will allow the accurate analysis of an urban condition so as to provide intervention methods to improve the thermal performance of the built and unbuilt environment.

Case Study: Cairo Slums

We are using Cairo (Egypt) as the location of our project. Cairo is located in a hot arid climate where cooling is needed most of the year to achieve thermal comfort.

Although Cairo has historically witnessed a large range of passive architecture innovations to address the hot dry climate, today, modern architects ignore these techniques. Instead of using wind catcher, roof lanterns and Mashrabiyas, nowadays everything is substituted by the HVAC systems. The residential building industry is responsible for the 43% of the total energy consumption of Egypt, which increased in the last five years. This caused the government to cut the electricity in all districts of Cairo in an average of 2 hours a day in summer and half an hour a day in winter in the last two years.

We are choosing slums in Cairo in particular for a context for our study, mainly for the alarming growth rate or these settlements, which is clearly out of the government’s control. The Egyptian Housing Ministry estimates that 40% of Cairo’s population is living in slums.

It became a fact that it is not only impossible to remove the existing informal areas, but also to very hard to control reduce the growth rate of these areas: this is the ugly truth.

Therefore, it became an urgent matter to study and research these slum areas and try to fix the problems on a larger scale with the available resources: the bare minimum. The slums areas have a lot of problems; we are aiming to passively solve the lack of ventilation/thermal comfort for people to have a ‘humane’ life.

Focusing on the morphology of the slums themselves, they are in a stagnant bath of unmoving air. Buildings are so close together and streets are so narrow that the air is literally forced into motionlessness. These conditions are unbearable for locals living without fresh air at the urban scale. In Cairo, the need is dire and with “Allometric Sake” we are providing solutions based on simple and economical architectures.

About the entrant

Amira Abdel-Rahman is a first year Master in Design Studies (MDes) candidate (technology concentration) at Harvard Graduate School of Design. She finished her bachelor’s degree at the American University in Cairo (AUC) (architecture engineering major, computer science and economics minor). After graduating, she worked for a year as a research and teaching assistant at AUC, as well as design team leader and computational designer at Dimensions Designs.

Amira believes that technology can be an enabler of innovation and creativity. In her study and research at GSD, she worked in several projects related to computational design, smart material and robotics.

Gabriel Muñoz Moreno is a licensed Architect with an Advanced Diploma in Digital Fabrication and candidate for a Master in Design Studies from Harvard University. With his work, Gabriel has won international awards and has exhibited in places such as Expo Milano 2015 and the UN-Habitat III conference. Moreover he worked in international offices such as Shigeru Ban Architects in Tokyo and Abalos+Sentkiewicz in Boston.

His research focuses on achieving a sustainable development between the natural and social environment due to the expected population growth. To do so Gabriel has designed alternative construction and urban systems focused in Asia due to its rapid growth. In the following years, Gabriel plans to expand not only the solutions but the locations of this research to other continents, trying to achieve an urban sustainability that also provides opportunity for its inhabitants.

In 2014 Gabriel co-founded Social Cooperation Architects, where systems and designs to solve some of the most pressing social issues are proposed.

Santiago Serna Gonzalez has a Bachelor’s degree in Civil Engineering from the University of the Andes (Universidad de los Andes) in Bogotá, Colombia. He practiced structural engineering from 2012 to 2014 at Proyectistas Civiles Asociados (PCA) and P&P Proyectos SAS in Bogota, realizing the construction industry needs a more emphasized social agenda for new projects.

Motivated to change the status quo, he entered the MArch I program at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) in 2014. Faced with ultimately conflicting perspectives of his newly found interest in architecture, he took a step back, and left the GSD on a leave of absence to work in a dairy farm in Colombia during the spring of 2015.

Currently, Santiago has transferred to the MDes Energy and Environments program at the GSD. Now, his work is aimed at the dissemination of novel energy ideologies and methods, researching vernacular architectures and high performance materials. Being able to combine design and engineering is his lifelong personal and professional goal. By doing so, projects can become integral to society, working across all scales, activating opportunities for the less fortunate masses.

Shelter Global Dencity Competition in 2016

Shelter Global, an architecture and design non-profit, are pleased to invite architects and students from all over the world to enter the second annual Dencity Competition. Last year the inaugural Dencity Competition had over 350 registrations from 50 different countries and the winners were highlighted in a number of publications.

The intent of this architectural competition is to foster new ideas on how to better handle the growing density of unplanned cities. Rapid world growth and urbanization is causing some of the densest places in the world to be comprised of makeshift homes, otherwise referred to as slums. Now, more than ever, architects and designers need to play a central role in the development of substandard neighborhoods.

Dencity has a prestigious jury of architects, professors, and thinkers from around the world. All competition submissions are due by April 25, 2016. Registration can be done online at:

Dencity Competition 2016

Location: Paris, France

RIO OLYMPICS: Sustainable Fanbox Competition

New Architecture Competition by archasm

Architecture Competitions

Architecture Competitions : links

NYC Aquarium & Public Waterfront Design Competition

NYC Aquarium Architecture Competition

Arquideas Central Park Summer Pavilion (CPSP) New York competition

Central Park Summer Pavilion Architectural Competition

2016 SEGD Global Design Awards

2016 SEGD Global Design Awards

Architecture in France

French Architecture Developments

Architecture Prizes

World Architecture Festival Awards

Comments / photos for the Paris Pavilion: The Art of Peace Competition Winners page welcome.