Designing for Extra Care: What Can Covid Teach Us?, Learning from the Pandemic, Design Guide Tips

Designing for Extra Care: What Can Covid Teach Us?

Dec 13, 2021

JDA Architects: Article

Extra care offers practical, progressive options for designing sustainable housing.

The impact of the pandemic on ageing populations in care homes has highlighted the care sector’s shortcomings and precarious economic position. Future care solutions must offer older people more choice as well as security. Extra care can do this.

But designing for extra care has wider implications for the post-Covid economy. It can support the growth of sustainability in housing.

Designing for Extra Care

What are the Care Consequences of Covid?

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted pressing issues around care and looking after the vulnerable.

When people were discharged from hospitals into care homes early in the pandemic, this had devastating consequences. But it also illustrated the shortcomings of conventional care accommodation.

In a typical care home setting, there is a general sense that residents lack agency. They are the passive recipients of care. Where things go wrong, they feel the full impact.

But care can take multiple forms, including arrangements that preserve people’s independence to a greater degree.

While Covid has brought deficiencies in care into sharp relief, it has also raised the issue of what forms of care should be on offer, and how to design for care in better ways.

The pandemic has hit the social care sector hard. How can it bounce back economically while also ensuring the best quality of life for its users?

The chief lesson for care after covid is that there must be more alternatives for users.

The demand for alternative care models such as extra care and specialist housing is booming, according to the Institute for Public Care (IPC).

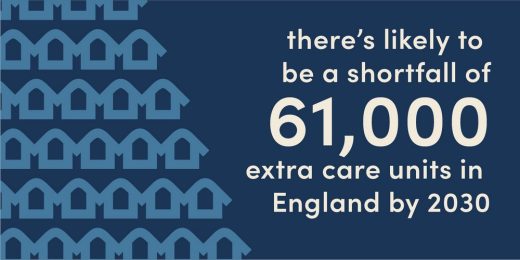

But when it comes to development, this more diverse approach to housing for care is still in its early stages. Supply and demand are not aligned. IPC says that there’s likely to be a shortfall of 61,000 extra care units in England by 2030.

Why is Choice Important for Older People?

Extra care is also known as assisted living and supported housing. It offers more choice to its end-users compared to traditional care models.

Typically, extra care accommodation is self-contained but with various support features that support independent living. This self-contained quality emphasises the home environment for users. But it also means that a one-size-fits-all approach isn’t appropriate.

If you’re going to help people maintain their independence, you need to make them feel like they can make clear choices about the character and design of their accommodation.

Context is crucial here too. What sort of community will the extra care accommodation be a part of?

Extra care environments can be apartments, bungalows or houses. Extra care may combine these various forms and range in size from multiple units to village-style environments that contain hundreds of homes.

These different environments must be adaptable to the individual needs of their residents and flexible in what they offer.

The aim should be for residents to live their chosen lifestyles as they age without facing too much disruption.

This is very much in contrast with the perceived passivity and loss of control associated with the traditional care home model.

Post-Covid, giving older people greater control over how they live is taking on a greater significance. We need to see this growing demographic not as potential victims but active individuals making active, positive choices about location and lifestyle.

How Should We Design for Extra Care?

Designing for extra care should be aspirational but realistic.

At the core of the extra care model is the concept of combining independent living with on-site support. But we think there must be an additional element to this community. This community element is achievable through true design quality.

The success of any extra care design doesn’t only rely on the design of individual accommodation units. It’s about creating a proper sense of place and authentic choice.

The challenge is to go beyond the basics to create an atmosphere where residents can thrive. We need to move from what’s viable to what’s desirable.

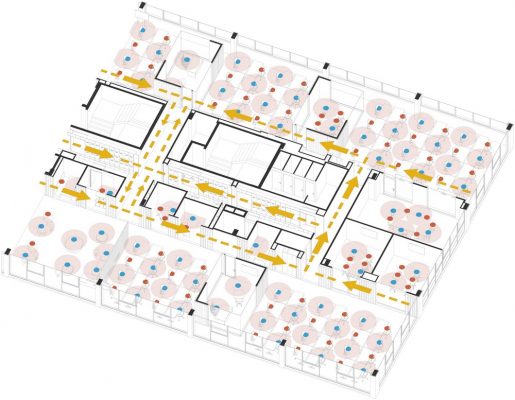

From its entrance onwards, the extra care scheme needs to lead residents and visitors through a sequence of spaces. These spaces should be high quality and allow residents to move seamlessly from the public domain. They should progress through several discrete gateways to more semi-public and private areas.

This is a kind of passive security, allowing residents to choose where to locate themselves – whether in the heart of a community bistro, a more private residents’ lounge or within their own homes. This choice should be something the resident can make absolutely for themselves.

Where there are communal spaces, they need to reflect an openness yet offer a sense of safety. This is essential for public health considerations, post-Covid, but also for establishing an environment that doesn’t feel institutional.

External and internal design quality is the key to this, offering flexible outdoor spaces that provide options for interaction or quieter periods. These outdoor options must interact with internal spaces that should offer movement and a lack of restriction.

The internal environment needs to heighten residents’ awareness, offering clear and understandable ways of moving around and through the building. The design and specification of extra care schemes should always promote independence in both thought and action.

Design, wayfinding and specification are not simply about acknowledging dementia-friendly box-ticking principles. They’re a way to create good quality environments and homes for all.

New extra care residents are no longer the Vera Lynn, World War II generation. People who were young in the Sixties are now looking at this type of accommodation. Our approach needs to reflect them and their aspirations. Only by doing this can we offer spaces that will appeal to over-55s.

It’s a question of balance. Residents need to feel they are a part of a real community where they can also retreat to their own private spaces.

The community was a central pillar of support during lockdown. This is another lesson for care after Covid. Older people choosing extra care are looking for supportive environments beyond their front doors.

How Can Extra Care Support Sustainability?

Sustainability isn’t only about environmental performance. There’s a housing shortage across the UK. One way of addressing this is to encourage more movement in the market.

Offering older people improved options for later living can help create a more sustainable housing market.

When we’re looking at design standards for extra care, we should be aiming to create housing that doesn’t compromise on design. Extra care housing schemes must meet users’ aspirations. This is about rightsizing rather than downsizing.

Rightsizing is a relatively new concept. It’s closely linked with notions of retirement and making decisions about later life. It requires building appropriate accommodation for older people in suitable locations.

This looks at the longer-term too. Rightsizing is about building homes to a standard that enables continued use, even when their occupants’ mobility reduces.

Rightsizing is one aspect of sustainability. Another is environmental social governance (ESG).

By following ESG principles, we can design sustainable extra care homes that provide excellent energy performance and meet the needs of their residents within a community setting.

These principles include environmental best practices, sustainability, good governance and ethical behaviour.

The Opportunity for Change

Covid has exposed structural weaknesses in the care system and made us question how we look after our ageing population.

There’s no easy answer to this question. But extra care should be part of a realistic solution to the care crisis and the housing shortage.

For more information about quality design for extra care and sustainable housing solutions, please contact:

Rob Henderson Managing Director

[email protected]

JDA Architects

Designing for Extra Care: What Can Covid Teach Us? images / information received 131221 from JDA Architects

COVID-19 Crisis Impact on Buildings

Pedra Silva Arquitectos Return-to-Office Consultancy

Return-to-office consultancy for Covid-19

Covid-safe Office Design

Design of a Covid-safe office

Post-COVID mixed-used developments

Rise of mixed-used developments post-COVID

How COVID-19 changes the way we work

How COVID-19 changes the way we work

COVID-19 Remote Working

COVID-19 Remote Working: Architects Impact

UK Construction Industry recovery news

UK Construction Industry recovery news

Rethinking design: Going viral – how the coronavirus will affect urban design

How COVID-19 changes urban design

COVID19 Impact on guest journey

How COVID-19 changes the way we work

Database for Quarantined Architects

Coronavirus Impact

The impact of coronavirus on the property market

Coronavirus on the property market

Coronavirus (COVID-19): UK government response.

Comments / photos for the Post Covid-19 workplace of the future page welcome