Shenzhen & Hong Kong Bi-city Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture 2017-2018, UABB News, Nantou

Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture 2017-2018 News

Bi-City Architectural Event in Hong Kong / Shenzhen, China, article by Carlos Teixeira, architect, Brasil

13 Jun 2018

Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture: UABB 2017

Cities within the City: the Shenzhen & Hong Kong Bi-city Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture 2017-2018

Article by Brazilian architect Carlos M Teixeira

A biennale that is a “revolt against a mainstream culture ruled by ‘centralism’” and that offers “a space of resistance against authoritarian planning”, that is how the Shenzhen Biennale’s curators presented the event’s current edition, which began in December and terminates in March this year.

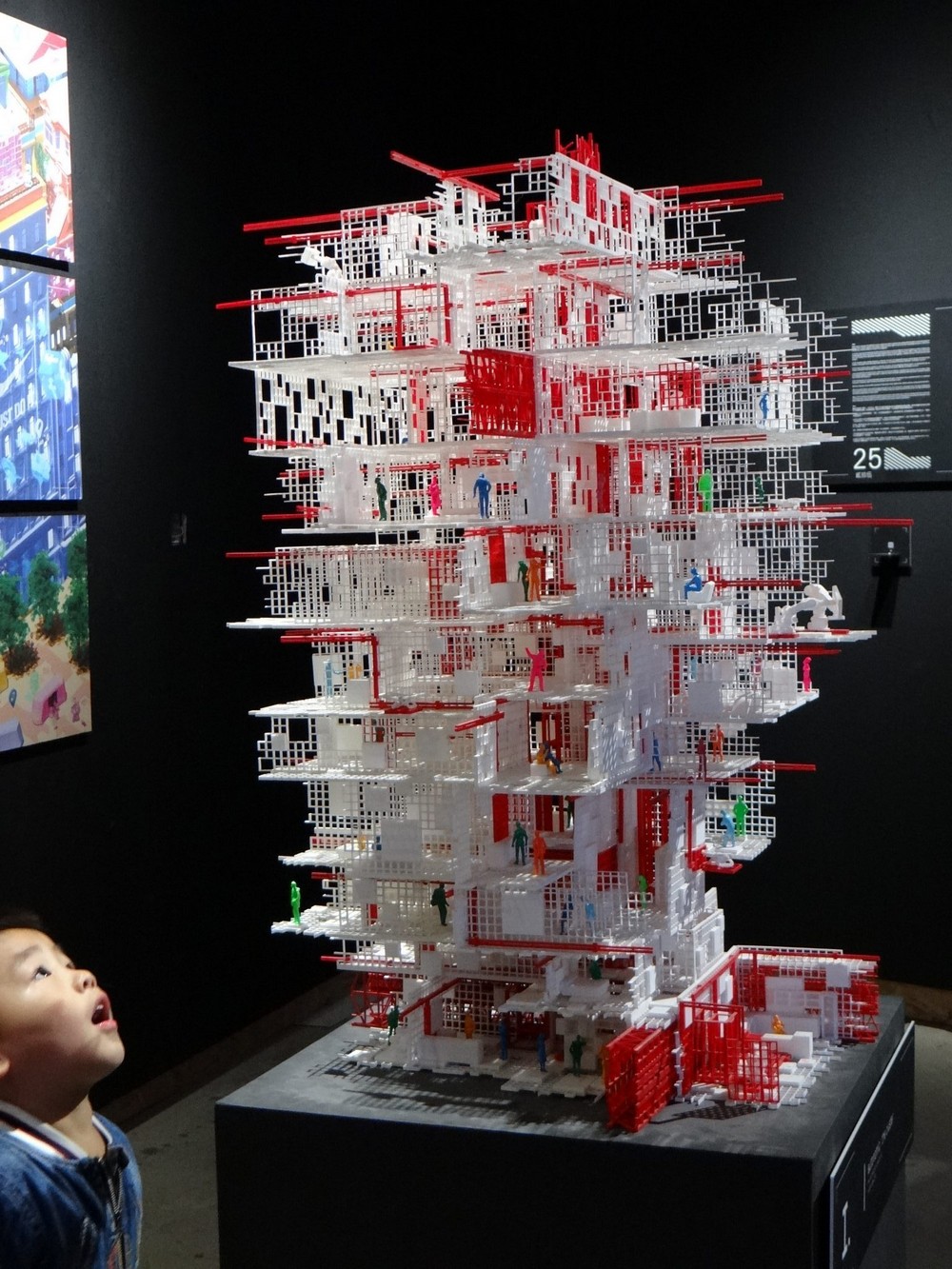

Autonomic by United-Make:

photos courtesy of Carlos M Teixeira

With a long and unwieldy name— Shenzhen/Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture—, it ended up being nicknamed the UABB. Held since 2005, this important international exhibition spanning the visual arts, urban art, architecture, urban experiments, workshops, seminars and temporary schools claims to be the world’s only urbanism biennial.

Indeed, this edition is essentially about urbanism, more specifically about the importance of the tightly-packed ghettoes of Shenzhen, the Chinese city that rose to fame for having ballooned into a metropolis in a single generation. Urban folklore has it that this city of 12, 15 or 20 million people, depending on which stats you use, was a town of just 30,000 inhabitants back in 1979. Shenzhen is the cradle of China’s electronics revolution: located at the strategic Pearl River Delta, the city was chosen by then-Communist Party Chairman Deng Xiao Ping as the site of the first Special Economic Zone (SEZ). Within a matter of years there wasn’t a nation on the globe that was immune to the fruits of that experiment. Shenzhen became the kernel of China’s “State capitalism”, home to an industrial park that would become the “world’s factory”, setting the development mold for the many SEZ that would follow. No matter where you are, some component or other of the electronics you use most likely came from the Shenzhen SEZ.

Atelier-Bow-Wow_Fire-Foodies-Club:

“With no origin, no history, and no culture”, Shenzhen is today a typical example of what China’s prosperous southern and coastal cities have become. As an improbable combination of two planning models—Soviet-style modernism and market utilitarianism—, Shenzhen is the typically bland city of the Chinese miracle, pretty much indistinguishable from the rest and scorned as a capitalist aberration bereft of any real identity. But this city—home to the giant Huawei, for example—has ample greenery, an extensive and efficient subway system, emblematic skyscrapers, busy high streets, well-tended landscaping, and electric busses, etc. And it all runs smoothly.

For the few foreign tourists who venture there, there are huge theme parks to visit, two of the most famous being Window of the World, with 130 miniatures of famous tourist attractions from all five continents, and Splendid China, offering up China’s own landmarks in miniature. There are also signature buildings by world-famous architects, such as the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (OMA), the Contemporary Art Center (Coop Himelblau), the OCT Loft (Urbanus), and the recently-inaugurated Victoria & Albert Museum (Fumihiko Maki).

West Village Basis Yard by Liu-Jiankun-Architects:

Urban Village

But the important point is that this edition of the UABB is not a celebration of any of that. It is a discussion on a subject little known outside of China: the hidden slums that are home to most of the migrant workers who pack China’s major cities, known by the oxymoron Urban Village, or Chengzhongcun.

In a communist country, there is no national housing policy to cater for the laborers and migrant peasants flooding the cities in search of work. The solution fell to the private sector, which began creating these hyper-dense inner-city villages to house these floating populations. Few know that the Pearl River economic miracle was not solely spurred by Hong Kong and its rampant opportunities, but was also driven by a perverse, yet self-regulating mechanism that cushions the many flaws and shortfalls of centralized policy and tackles top-down planning with street-level reactions.

In the words of the three curators Liu Xiaodu, Hou Hanru and Meng Yan, “The Urban Villages [are] an alternative model of the contemporary city[…] They have now become the “Arrival City”, where the exponentially growing number of new immigrants to a city reside.The urban villages covering about one-sixth of the total land area of Shenzhen house approximately nine million of the over twenty million people in Shenzhen. In other words, they accommodate 45% of the population with 16.7% of the space.” As an “extra-territory spontaneously formed and self-governed in a sense”, obeying a logic totally alien to the top-down, centralizing state model, the urban villages are genuinely inclusive and diverse in terms of space and community. “Under pressure from external forces, [the village] is forming spontaneously and evolving continuously, steered by its own self-reproduction and self-regeneration. Urban village is the last frontier of Shenzhen’s urban renewal campaign, and also the bottom line of a balanced urban development”.

Nantou is the name of the Urban Village in which the Biennale is held. In the 19th Century, it was the administrative seat of a region that also included Hong Kong, Macau and Zhuhai. Hong Kong seceded after the Opium War in 1840, sending the village’s importance into sharp decline. The oldest of the Shenzhen Urban Villages, Nantou has ruins dating back to 1700 years packed in alongside the 20th-century remnants of a pre-revolutionary past, the Maoist heritage and the economic structure of a thriving SEZ.

You can find a little of everything in its bustling back alleys: restaurants, workshops, tenements, temples, schools, factories and hundreds of “handshake buildings”—ten-storey apartment blocks stacked so close you could reach out the window and shake the hand of your neighbor across the way. Interestingly, these residential stopgaps that welcome the immigrant workforce with open arms is also one of the few city spaces that are entirely owned by the private sector. Like the Latin-American shantytown stood on its head, here the clandestinity coincides with the few parcels of land that have escaped the clutches of the CCP. In Latin America, we’re used to seeing the Barrios and Pueblos Jóvenes encrusted on public land; but here, the slums rise on private property.

Everywhere you look there’s electrical wiring, water pipes, clotheslines and trinkets hanging in the windows, yet this tangled cityscape is far better integrated into the city system than, say, a Brazilian favela. Chengzhongcun segue into official city blocks with no social tension, and the Biennale’s omnipresence throughout the four corners of the city furthers that integration. To the visitor, the cacophony of Nantou is like music to the ears after the hum and whirr of the shopping malls and condos of postcard Shenzhen.

According to the architect Juan Du, a lecturer at Hong Kong University, about to publish a book about the Urban Villages, long before the SEZ, hundreds of thousands of peasants tilled the arable land around the market towns of the Delta. During Mao Tse Tung’s Great Leap Forward, the lands around Nantou were collectivised into an agricultural commune. Later, the villas merged into each other, complicating the agrarian issue still further. “It is thanks to the ambiguity surrounding land ownership that the Urban Villages have been able to last this long”.

Meng Yan, one of the Biennale’s curators, explains the land issue more clearly: “The original rural land under collective ownership was expropriated and converted to state-owned property. Villagers lost their farmland but still retained their rural residential plot, and when they saw the large influx of immigrant workers, and the subsequent surging demand for rental housing in the high-speed urban expansion, they started to expand their private residential buildings for rent.”

It was then that the villagers, whose local planning ordinance only permitted two-storey homes, transformed their residences into ten-storey tenements. To milk every yuan out of their lots, they expanded their properties outward and upward, resulting in the handshake buildings, and so, from the 1980s on, migrants came to outnumber the increasingly rent-rich villagers, who moved into more affluent neighborhoods.

Teetering somewhere between chaos and order, legality and illegality, solution and problem, Nantou somehow escaped the radar of the dreaded Central Propaganda Department, the state organ that decides what the press cannot say in its daily coverage. Hence these stacked-up enclaves obtained scant mention in the Chinese and also western media, which led to pressure from the real-estate market steamrolling the country and leaving towers and malls in its wake, not only razing the architectonic past of whole cities, but contributing to the spiritual void into which contemporary Chinese society has sunk.

Like Shenzhen, the chengzhongcun may not be a model, but, until quite recently it was considered only a matter of time before they disappeared. By questioning the validity of the Chinese urbanization model and lauding a city that celebrates its differences (the UABB’s title is “Growth in Difference”), the Biennale is certainly another good argument toward convincing the local authorities that it’s time to look for new ways forward.

The Biennale in Nantou

The installations are scattered across the five zones of Nantou, including factories, streets, residential buildings, parks and heritage sites, and the event itself has been embraced as a means of valuing the village and standing against its imminent demolition. The flagship exhibition is held in a factory complex in the north, and is divided into three sections: Global South, Urban Village and Art Making City.

Naturally, the largest of these is Urban Village, which presents research, case studies, open calls and a compilation of the vast number of projects carried out on the theme at Chinese and foreign universities. It seems that all the exhibition’s possible angles have been covered, with subdivisions including Urban Village Picture Book, Urban Village Photo and Video Room, Urban Village Databank, Urban Village Library, Urban Village Info Center, Urban Village Lab, Urban Village Voice etc. Architects from Colombia University presented Data-mining the Urban Village, an installation that has been trawling the social media and academic and journalistic sources for mention of the Urban Villages since 2001 in order to gather together the available literature. The result is a three-dimensional timeline made out of piles and piles of paper—some 400,000 pages in all.

The biggest of these exhibitions, Documenting Urban Villages, by the architect and researcher Juan Du, presents an evolutional panorama of Shenzhen’s 10 villages, including West Gangxia, partially demolished in 2009, and Baishizhou (population of 150,000), which had some buildings torn down in 2016 and has since lived under the constant threat of the wrecking ball.

This section also includes a physical interventions laboratory, introducing new features and amenities to the village, re-qualifying some of its residential buildings, and constructing a nice Community Center. The Center and squares are coordinated by Urbanus, by the architects Liu Xiaodu and Meng Yan, the Biennale’s curators, who showed the same mastery in choosing their intervention sites as they did the event’s conceptual framework.

But there are other themes too. The section Global South: Influence and Resistance gathers urban experiences from Kenya, Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, Cuba, Mexico, Macedonia and Southern China. In principle, it lends voice to a new global order that is forming among emerging countries together comprising a parallel and independent transactions network that dispenses with the cultural and economic gatekeeping of the northern powers. The curatorship is somewhat superficial in classifying South-American settlements as “a means of resisting the orthodoxy of the North”, but at least the theme is one that could potentially be developed elsewhere, and with less pedestrian curatorship. Curiously, the multi-billion-dollar projects the Chinese government is currently pursuing in Africa are a conspicuous absence in the exhibition. Cities, railroads, factories, ports and mining complexes in Namibia, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, Nigeria, Angola and Ethiopia, etc., are being built as we speak with Chinese money (and, in many cases, manpower).

Curated by Hou Hanru, curator of the MAXXI Museum in Rome, the section Art Making City presents a series of installations, videos, murals and performances that reflect how the artists in this Biennale (most of them Chinese) use the streets as an intervention site, broaching issues of individual freedom in public space and enlisting the participation of the locals. On opening day, the artist Lin Yilin occupied a high street in Nantou with a line made of merchandise from the street’s stores—vegetables, electronics, bowls of noodles, canned foods, slab of meat, fish, etc. Some of the local storeowners didn’t want to participate, so the artist hired people to lie down and take their “place” in the line. Yilin is known for the performance “Safely Maneuvering Across Lin He Road” (1995), in which he raised a brick wall and moved it along with him block-by-block as he made his way across a busy road in Guangzhou.

Glasnost

However, it would seem not all the authorities are happy about this Glasnost. On opening day, the artist Hu Jiamin was arrested because his mural, a triptych laid out at the entrance to a factory complex, contained a surrealist painting with an empty blue chair in the middle. The chair alludes to the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize awarded to the political activist Liu Xiaobo, who was arrested that same year and so could not attend the prize-giving ceremony in Oslo. He asked to be represented in absentia by a blue chair.

The following day, it was the turn of the artist Jiang Zhi, whose piece “One Photo of Firework” was removed from exhibition at one of the factory-galleries. Part of the Art Making City section, the photo reappeared two weeks later only to be removed once again ahead of an official visit by Shenzhen authorities. The peculiar thing here is that the same artwork had already been shown in China without any trouble, proof of the fickle nature of the Chinese censors.

Lastly, one of the architectonic interventions in the Urban Village exhibition is Nantou Playground, proposed by us, Vazio S/A, but left unbuilt for “political reasons”.

The playground was to be installed at an abandoned building that had been constructed without planning permission. It was presented to us by the curators in mid 2017, in the form of photos and drawings. So we had two overlapping liberties on our side: total ignorance of the context and carte blanche to do what we liked.

The many kids in the streets and the lack of public spaces in Nantou suggested to us the need for a playground stuck in amongst those concrete ruins. Like mixing oil and water, the challenge behind Nantou Playground was to retain something of the place’s grittiness and the savage textures of its wear and dilapidation whilst conjuring the magical, festive atmosphere of a play area. It was our option for grittiness that suggested our palette of materials: steel netting and plywood sheets; elements sufficiently delicate not to obscure the enchantment, silence and reticence of the abandoned building. As a counterweight to all that hardness, warm playground colors brighten the existing concrete grey, while the various slides and rides transform the bare and sombre platforms into play pens.

According to the assistant curator Yin Yujun, Shenzhen City Hall prohibited all new construction in the Village in 2005 in a bid to curb the rampant verticalization going on with the bizarre handshake buildings, but the owners went ahead with the construction anyway, before being shut down. And so the shell-work stood idle for years on end until the Biennale presented our playground project to the authorities in September 2017 and received the initial go ahead. So we developed the plans, the model, details, prototypes and then… permission was withdrawn.

Architect Carlos Teixeira works for Vazio Arquitetura in Brasil

Location: Shenzhen, China

Brazil Architecture

Entre Book – Carlos Teixeira

photograph from publisher

21 Dec 2017

Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture UABB 2017

MVRDV and The Why Factory participate in the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen) 2017

MVRDV and The Why Factory stage a series of interventions for the Seventh Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen) (UABB) jointly curated by curator and critic, Hou Hanrou and founding partners of URBANUS, Liu Xiaodu and Meng Ya.

16 Oct 2017

Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture in Shenzhen

Nantou Old Town – Aerial View:

Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture: UABB 2017

Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture: UABB 2015

picture courtesy Shenzhen & Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of UrbanismArchitecture

Shenzhen Architecture Biennale

SZHK Architecture Biennale UABB 2013

Shenzhen Architecture Biennale UABB

Shenzhen Hong Kong Biennale

picture : 2011 Shenzhen & Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of UrbanismArchitecture

SZHK Biennale Installation by Ball Nogues Studio:

photo : Benjamin Ball

SZHK Biennale Installation 2009 Bug Dome by WEAK!

photo © Marco Casagrande

Architecture in SZHK

Hong Kong Architecture Designs – chronological list

Business of Design Week Hong Kong

Shenzhen Buildings

picture © MVRDV

Universiade in Shenzhen

von Gerkan, Marg and Partners (gmp)

photo © Christan Gahl

Universiade in Shenzhen

Hong Kong Architecture

West Kowloon Development

Foster + Partners

image from architect

West Kowloon Cultural Complex

Innovation Tower, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University – PolyU

Zaha Hadid Architects

image from architect

Hong Kong University Building

Website : UABBHK – Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (HK)

Comments / photos for the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture 2017-2018 page welcome