Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part Three, Modern Scottish Architecture, Architectural Education Dissertation

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Building Study Part 3

29 November 2021

Third Year Architectural Dissertation by Daniel Lomholt-Welch, Scotland

Daniel Lomholt-Welch

Architecture MA(Hons) Dissertation

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Building – Illeity, Idolatry, and a Thing that Leaks

3. Illeity, Idolatry, and a Thing that Leaks

In his essay ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’, published in 1954, Martin Heidegger introduces the concept of ‘the fourfold’, or Geviert in his native German. It is a concept that has remained elusive since he first postulated it, and therefore is a subject of much debate amongst philosophers.[1] Within it are aspects that take on mystic dimensions, which can cause doubt to arise amongst the mainly secular Western school of thinking. However, Heidegger uses these dimensions in a specific way and with a certain purpose.[2] Heidegger’s theory states that the world is comprised of ‘things’, each of which may allow a human to feel nearer to their own existence, a nearness which he claimed was diminishing due to the rise of modernism. This ability for a ‘thing’ to provide humans with this proximity to themselves is based on a set of preconditions, namely, the fourfold. The fourfold consists of earth, sky, mortals, and divinities. These are placed upon two intersecting axes, that of nature (earth, sky) and that of culture (mortals, divinities).[3] It is by gathering the fourfold that a ‘thing’ is said to be ‘thinging’, derived from the High German etymology of ‘thing’ (Ding) which also means ‘to gather’.[4] Heidegger saw these terms as being inextricably linked. ‘A thing’ was not to be seen as ‘an object’, but something with the capabilities to gather the fourfold. By gathering, it was not necessary that the elements were physically proximate, but that they were near in terms of what he called ‘nearness’, that being people’s conception of what was potential to their existence.[5]

He uses the example of the common jug. The jug, by being made of the matter of the earth, by being ‘under’ the sky, and having the potential to be utilised for drinking from (mortals), or being used for libation (divinities), thus has the potential to gather the fourfold, and was therefore ‘a thing’.[6] Heidegger’s usage of the terms ‘mortals’ and ‘divinities’ can seem fairly complex, but it is possible to say that the divinities can be seen to be an inescapable dimension of mortals. That is not to say that mortals are divinities, or that divinities are mortals, but that through their imaginations, mortals can give place to divinities. By claiming that the divinities are an inescapable dimension of mortals, it rejects any form of hierarchy applied by organised religion.[7] It is clear that such loaded terms as ‘mortals’ and ‘divinities’ can cause due consternation to those attempting to make sense of the fourfold, however Heidegger did use these terms for specific reasons. The term ‘divinity’ represents a nomination that is distinct, and non-relational. ‘God’ never speaks back. Arguably this highlights an ‘absence of the presence of transcendence’ and creates a duality of the world as either possessing the transcendent, or lacking it, hence the usage of the terms ‘mortals’ and ‘divinities’.

An issue with Heidegger’s theory is the concreteness of the number of folds. He specifies four, however there is little basis to say that this denomination is true, or plausible in any sense. According to Julian Young, there exists at least a fifth dimension of the fourfold, that of the holy. To Young, the presence of this dimension is based on Heidegger’s own claim that in order for a lifeworld to be a place which can accommodate ‘dwelling’, it must preserve the dimension of ‘the holy’. Heidegger notes that this dimension can only be ‘measured’ by the poetic, a subject he discusses in his essay ‘Poetically Man Dwells.’[8] But how do we get any clear definition of his term ‘lifeworld’, or how presence is given to the holy? To which axis of the four(five)fold would the holy belong, and in what way does it interrelate with the other four folds? The theory of the fourfold is nebulous, vague, and leaky. It leaks, much like the decaying matter of Saint Peter’s Seminary leaks.

The high altar at Saint Peter’s Seminary (Fig 1.) was an example of ‘a thing’. A chthonic element, it thrusted up from the ground, emphasising the qualities of the earth. Illuminated from above by a ziggurat glass roof, light was also a key element in the sanctuary space, which highlights the presence of the sky. And much like Heidegger’s jug, the altar had a clear ability to gather both mortals and divinities together. Therefore, according to Heidegger’s theory, it allowed humans to feel nearer to their own existence. It was a highly emphasised architectural manifestation of the gathering of the fourfold, however the altar was far from the only ‘thing’ present in the Seminary: the side chapels, the crypt, and even the study bedrooms all had the potential to gather the fourfold. In fact, the Seminary abounded with ‘things’. One could even go as far to say that the entire building constituted a ‘thing’ due to its ability to gather the fourfold – Heidegger places no distinction between what would be considered an object, or what would be considered a space, when assessing its ability to be a ‘thing’. Each of the aforementioned ‘things’, whether a space with expressed limits or an object of solidity, have their own respective literal or metaphorical voids. What was key in the consideration of a ‘thing’ was its potential. The French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty asserts that we perceive the whole before the parts, giving primacy to bodily senses over reason. It follows that since we are also aware of our bodies, we relate the world to our bodily capacities. Our primary interest lies not in what the world is, but rather what we can do with the world.[9]

In addressing the Seminary in light of Heidegger’s theory, it is interesting to revisit the example of his jug, and importantly the presence of its void. As a functional building, the seminary is quite an accomplished gathering of the fourfold, in its delicate treatment of light, chthonic forms and highly ritualised planning. Clearly paying homage to the works of the modernist architecture of Corbusier, it ironically contradicts Heidegger’s claim that modernism has distanced ourselves from our own existence. This claim leads to speculation of modernism’s inability to gather the fourfold, however the Seminary clearly shows otherwise. As Patrick Nuttgens explains, ‘the whole building is an architectural expression of its liturgical function, a house of God where living, contemplation and working all combine in a single act of worship’.[10] In similarity with the aforementioned jug, the working Seminary could have been said to be full, with its contents potential for worship resembling the jug’s contents for potential libation. As a derelict building, it could be seen to contain a void, a receptacle awaiting use. Heidegger asserts that the jug remains a ‘thing’ whether full or not; the same could potentially be said for St Peter’s.

In light of the Seminary’s deconsecration and subsequent ruination, the validity of many of its elements as ‘things’ is perhaps compromised due to the lack of active belief, and ritual participation within it. This has arguably diminished the presence of ‘mortals’ and ‘divinities’, resulting in a sense of illeity, the absence of transcendental presence, a concept developed by Emmanuel Levinas. He states that God is rarely manifested in the ways we desire, and only leaves a ‘trace’ of his manifestation behind.[13] A visual reminder of this diminished presence of mortals and divinities is the broken high altar (Fig 2.), its chthonic strength vanquished, drawing attention to the debatable presence of the fourfold within the Seminary in its current state. The Archdiocese of Glasgow’s decision to jackhammer the altar to pieces in 2015 to prevent the continuation of profane acts upon it such as barbecues, graffiti, and rumoured pagan rituals had the result of damaging the manifestation of the ‘earth’.[14] The fracture of the altar, much like the deconsecration of the building 35 years earlier, were not rituals of celebration for the church, in fact quite the opposite – they were rituals of shame and an acknowledgement of the building’s failure.[15]

Even the manifestation of the ‘sky’ in the sanctuary space has changed as the building’s fabric has deteriorated. As the roof has collapsed, leaving only charred timbers bearing traces of arson, the space has opened up to the sky. Mircea Eliade highlights this quality of the ‘hypaethral’ as being characteristic of the earliest spiritual sanctuaries, their opening to the sky representing a breakthrough from one plane to another, enabling communication with the transcendent.[16] What the dereliction of the sanctuary, and in particular the altar, represents is the destruction of the ‘axis mundi’. Eliade hypothesizes the concept of the axis mundi as being a vertical feature that linked all three cosmic levels together: heaven, earth, and underworld. The architecture of the altar presented itself as an axis mundi, a spiritual centre of space according to Eliade. By destroying it, he would assert that the link between the three cosmic levels is therefore broken.[17] However the sanctuary and its destroyed altar remain a focus for those who seek to repurpose the Seminary. The continuous efforts to revive the building to a new purpose support the notion that it still holds potential, not the original potential of the building, but potential nonetheless. Heidegger’s theory fails to give much clarity on the impact upon ‘the thinging’ of the seminary in its current state. Indeed, it still holds the physical potential to be a gatherer of the fourfold, however fanciful it is to conceive of a mass being held amongst the ruins of the altar. But very few people would attach those kinds of values to the hulking mass of concrete now.[18]

There is no doubt that Heidegger’s theory of the fourfold makes an interesting case. It highlights the role that our environment plays in our lives, and how certain elements within them are appropriated by our perception of them. However, adopting Heidegger’s theory of the fourfold brings with it certain issues. By placing such importance on the role that these ‘things’ have by claiming them to be responsible for the gathering of earth, sky, mortals and divinities, we negate these element’s ability to give presence to themselves without the ‘thinging of a thing’.[19] This can result in idolatry, to suppose that divinities are dependent on ‘things’ in order to bring about their presence in the world, and the assumption that their presence is in a specific place. Thus the ‘thing’ by its containment is seen as an idol due to its ability to gather the divinities. In specific terms, the god is not represented or signified by the idol, but is embodied by it, and is therefore able to witness any act of devotion to the god by mortals in its presence. According to Levinas, the irrefutable transcendence of God stresses that God is not an idol and cannot be seen or perceived.[20] The link between idolatry, at least in the traditional sense, and architecture, has been well covered by writers such as Joseph Lyle in his Paradise Lost.[21] However Saint Peter’s constitutes a building that is no longer the site of the idolisation of God, but idolatrous attitudes concerning the state of the architecture. What the building is, objectively speaking, is a large abandoned concrete structure in a forest nearby a small village. But the subjective opinions relating to it often speak of it as much more than that, sometimes going as far as to portray it as some form of exalted architectural realm.[22] The design of the building is mentioned frequently as deserving better than its current dilapidated state, with some seeing this as a desecration. This implies that the architecture itself is sacred to some, its decay meriting offence. It is interesting to note that very few see it as a religious desecration, thus calling into question Van der Leeuw’s belief that ‘the consciousness of the sacred character of the locality that has once been chosen is, therefore, always retained.’[23] In fact, what could be seen to have caused such a decomposition of the Seminary as a ‘thing’ would be the reorganisation of the presence of mortals, divinities and even earth within the building. No longer is the building a space purely for those of a very specific faith, but an indeterminate space ‘open’ to all. Again, the singular fragments into the plural. The variety of mortals that present themselves in the Seminary is much greater, each with their own purpose and ideals of the space’s potential, as per Merleau-Ponty.[24] This suggests the potential for the fourfold not only to be gathered in the ‘thing’ but to actually be able to reform the ‘thing’ itself.

This continued idolatry, although not of a conventional form, presents a challenge to Heidegger’s theory of the fourfold: what drives the reconstruction of a certain phenomenon of the gathering of the fourfold? Is it the reformation of the ‘thing’ itself as an entity, its values and potentials remade in the process? Or is it actually the fourfold’s constituent elements that are re-orientated and gathered within new things that drive this process?

[1] Markus Weidler, “Critique of Idolatry,” in Monatshefte 104, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 489.

[2] Adam Sharr, Heidegger for Architects (London: Routledge, 2007), 24.

[3] Julian Young, “The Fourfold,” in The Cambridge Companion to Heidegger, ed. Charles B. Guignon. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 377-8.

[4] Sharr, Heidegger for Architects, 26.

[5] Sharr, Heidegger for Architects, 25.

[6] Sharr, Heidegger for Architects, 33.

[7] Weidler, “Critique of Idolatry,” 490.

[8] Julian Young, “The Fourfold,” 375.

[9] Jonathan Hale, Merleau Ponty for Architects (London: Routledge, 2016), 74.

[10] Karen Wenell, “St Peter’s College and the Desacralisation of Space,” in Literature and Theology 21, no. 3 (September 2007): 263.

[11] BBC News, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/in-pictures-38884020

[12] Design Curial, http://www.designcurial.com/news/art-therapy-bringing-st-peters-seminary-back-to-life-4860550/

[13] Michael L. Morgan, Discovering Levinas, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 300.

[14] Refer to survey

[15] Wenell, “Desacralisation of Space,” 268.

[16] Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and The Profane, trans. Willard R. Trask, (New York: Harcourt, 1959), 146.

[17] Eliade, The Sacred and The Profane, 20.

[18] Refer to survey

[19] Weidler, “Critique of Idolatry,” 491.

[20] Anselm K. Min, “Naming the Unnameable God: Levinas, Derrida, and Marion,” in International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 60, no. 1, (December 20006): 104.

[21] Joseph Lyle, “Architecture and Idolatry in Paradise Lost,” in Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 40, no. 1 (Winter 2000)

[22] Refer to survey

[23] G. van der Leeuw, Religion in Essence and Manifestation: A Study in Phenomenology (trans J.E. Turner; London: George Allen & Enwin, 1938), 393.

[24] Hale, Merleau Ponty for Architects, 74.

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study – introduction

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 1

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 2

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 4

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 5

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Conclusion

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Dissertation by Third Year Student at Edinburgh School of Architecture information / images from Daniel Lomholt-Welch

Edinburgh School of Architecture Student Projects

Second Year Student Projects at Edinburgh School of Architecture

Second Year Student Projects at Edinburgh School of Architecture

First Year Student Projects at Edinburgh School of Architecture

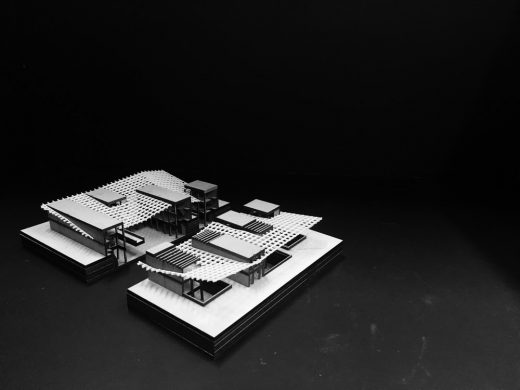

image courtesy of D L-W

First Year Student Projects at Edinburgh School of Architecture

Education Building Designs

New Macallan Distillery in Speyside

Design: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP)

photo © Simon PricePA Wire

Architecture and Landscape Architecture | Edinburgh College of Art

Comments / photos for the Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 3 page welcome