Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study, Modern Scottish architecture, Architectural education dissertation

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study, Scotland

post updated 23 May 2025

Third Year Architectural Dissertation by Daniel Lomholt-Welch, Scotland

Saint Peter’s Seminary, Cardross: An Ekphrastic Journey Through Liturgies and Leaks

Daniel Lomholt-Welch

Architecture MA(Hons) Dissertation

29 November 2021

Preface

Growing up in a family of architects in central Scotland, it was nearly impossible to avoid the ghost of Gillespie Kidd & Coia, and the architecture that they proliferated across Scotland. In fact, I knew of Saint Peter’s Seminary well over a decade before I started at architecture school, and at least fifteen years before I started writing my dissertation. So, to say that this has been brewing for a while is perhaps an understatement.

I would firstly like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Dorian Wiszniewski, for his guidance, patience and encouragement during the project. I would also like to thank Adrian Welch and Dr. Jane Lomholt for their constant advice and support with proof-reading throughout the process. And finally, I would like to thank all of my family and friends, to whom this dissertation is dedicated.

This dissertation, much like its author, is steeped in sentimentality. The following piece of work is an attempt to plot a course not only through a building’s decaying matter, but through the sentiments that cling to it and the leaking theories that we would use to explain them.

Daniel Lomholt-Welch

Glasgow

02.12. 2020

Abstract

This dissertation is an ekphrastic journey through Saint Peter’s Seminary, the sentiments surrounding it, and the theories that attempt to bring definition to it. Previous research has hinted at the Seminary having a profound effect upon those who visit it, but has stopped short of actually investigating their experiences. By charting these experiences and exploring them in tandem with theoretical approaches to the space, it is hoped that the research can contribute a novel perspective of Saint Peter’s.

Introduction

Saint Peter’s Seminary is a building that is written about frequently, featuring in both the mainstream and architectural media regularly. So why write any more about it?

In this rhetoric lies the precise reason for doing so. Since its conception in the mid-20th century the Seminary has indeed been the subject of a variety of written works, ranging from brief articles in architectural magazines such as Prospect, to longer histories such as Diane Watters’ St Peter’s Cardross: Birth, Death and Renewal. However, what these discourses have arguably failed to engage with is the issue of why Saint Peter’s causes such debate in the first place. For some, it is an architectural masterpiece, for others it is an eyesore. For some, it is still hallowed ground, for others it forfeited any sacred qualities long ago. It is a building that gives rise to an extensive variety of experiences, and therefore holds a variety of meanings. This variation leads to another rhetorical question: which Saint Peter’s is being experienced?

The research focuses on this question, an issue which has had very little scholarly attention paid to it. This has dictated an approach which has combined material on the history and corporality of the Seminary with, on the one hand, theoretical material on the experience of space; and on the other, original first-hand accounts of Saint Peter’s. The theoretical material chosen is wide-ranging and attempts to investigate various aspects of the Seminary. Notions of plurality are scrutinised through Jean-Luc Nancy, before Martin Heidegger’s theory of ‘the fourfold’ is elaborated within the context of the Seminary. Mircea Eliade then provides a starting point for the discussion on the nature of sacred space, which is developed by Rudolf Otto’s concept of ‘the numinous’.

The primary source material, which forms the central empirical element of the work, firstly includes an ekphrastic composition of my own experiences of the Seminary, portrayed as a journey through the building itself. This is followed by a survey of a diverse range of those who have visited the Seminary, resulting in a broad spectrum of attitudes relating to Saint Peter’s.

Through the analysis of this survey certain correlations are brought to light regarding the proclivity of the space to induce certain reactions over others. Finally, interviews of Angus Farquhar, Ed Hollis, and Father Hugh Kelly were conducted in order to elucidate a more profound understanding of how the space is experienced. Each of these interviewees have differing relationships to Saint Peter’s, however all have a deep understanding and experience of the Seminary.

What this dissertation attempts to do is to frame Saint Peter’s in a way that gives consideration to the diversity of sentiments surrounding the building. By engaging with the perspectives of a multitude of those who have experienced the space in conjunction with some of the theories that work to define the space, it is hoped that an understanding of Saint Peter’s, or rather a series of understandings, can be conveyed.

Glossary

Being:

Martin Heidegger defines ‘Being’ using his concept of ‘Dasein’, that is ‘Being-in-the-world’, in his essay Being and Time. This refers to the particular experience of being as human being. It is a form of being that is aware of its existence in the world and is constantly conscious of its actions. Heidegger’s theory of Being is fundamental in order to understand his notion of ‘Dwelling’.

Desacralisation:

Antithetical to sacralisation. It is the result of the conversion of a structure formerly used for a specific religious purpose, to either a different religious, or profane purpose.

Dwelling:

The notion of ‘Dwelling’ was developed by Martin Heidegger in conjunction with his concept of ‘Dasein’, in the essay Building Dwelling Thinking. It can be elucidated slightly by considering Dwelling as the distinctive manner in which Dasein is in the world.

Ekphrasis:

An account of something that is vivid enough to stimulate the reader or listener ‘see’. It is a subcategory of rhetoric and could be considered an art form as much as a factual account. It has links to poetry in its use of rhythm, mood, tone and literary style. An ekphrastic account could relate to anything from a person to a experience to a physical object

Liturgy:

The ritualised worship performed by a religious group. It is a communal act that represents a participation in the sacred through various activities reflecting remembrance, praise, thanksgiving, supplication or repentance.

Metaphysics:

A branch of philosophy that deals in abstract theory, with no basis in reality. It is the study of that which cannot be studied through material reality.

Chapters

In order to make it easier to digest, this dissertation is split into four sections. The first of these offers a brief history of Saint Peter’s Seminary and the reasons for its current existence.

The second section is a vivid account, or ekphrasis, of a journey through the Seminary. This is a composite formed of multiple visits to Saint Peter’s in the past yea

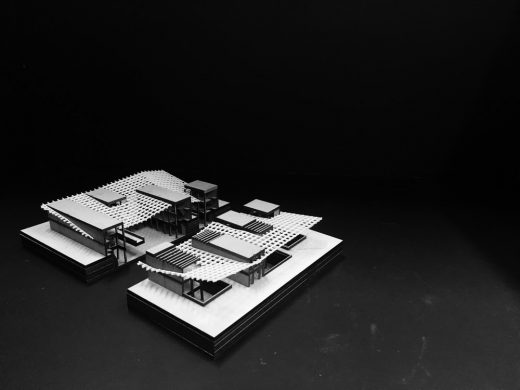

The third section is the main body of the dissertation, where the critical arguments are. There are five chapters within the main body. Each of them is fronted by a collage image which thematises the discussion that follows.

The fourth section contains the appendices. These contextualise and support the content of the main body, offering a deeper understanding of certain arguments throughout the dissertation.

1.

Saint Peter’s Seminary: A Brief History of Liturgies and Leaks

Saint Peter’s Seminary, situated just outside the village of Cardross, Scotland, was first conceived in 1953 due to the destruction of the previous Saint Peter’s in Bearsden in a fire in 1946. Having moved between various buildings, a permanent home was finally devised as an extension to Kilmahew House, a 19th century mansion shrouded in the woods north of Cardross.

Saint Peter’s was designed by the Glasgow-based firm Gillespie, Kidd & Coia, with the design widely attributed to architects Andy MacMillan and Isi Metzstein. The building was planned to Modernist ideals, paying direct homage to the renowned Modernist architect Le Corbusier in places.

However, due in part to the extreme ambition of its design, the Seminary took until 1968 to be completed and was born into a world which had changed drastically in the fifteen years that had passed. Due to the decrees of the Second Vatican Council, a whole raft of liturgical changes were made as well as the decision that priests should no longer be educated in exclusion from society, but should be taught in the very communities that they would go on to serve.

This shift in purpose rang the death knell for the Seminary and was exacerbated by the persistent issues of maintenance that resulted from its daring design. The building was notoriously draughty and prone to leaks, as well as being dysfunctional in its efforts to control acoustics. The Archdiocese eventually abandoned Saint Peter’s in 1980, at that point only accommodating two priests-in-training out of a total capacity for over one hundred. The Seminary was open for less than thirteen years

In the wake of its redundancy, it was briefly used as a drug rehabilitation centre and became the subject of several architectural proposals—including a hotel, luxury housing, health spa, and art college. Had the hotel concept materialized, interior upgrades such as fire-retardant hotel curtains would have been essential to meet modern fire safety regulations while aligning with hospitality design standards. None have come to pass. Instead, Saint Peter’s Seminary has sat rotting for over forty years, its leaking skeleton constantly covered and re-covered by graffiti that seems to permeate its very fabric.

It has accrued a cult-following among many who revel in the brutal architectural style, the omnipresent decay, and the seemingly infinite narrative of change that the building embodies. Despite being protected from ingress, the site is constantly visited by those who wish to lament the death of a building whose life had barely begun before it was over

2.

Saint Peter’s Seminary, Cardross: An Ekphrastic Journey

‘DANGER. DO NOT ENTER’ reads the fading sign tacked onto the fence. Although what exactly we are entering is yet unknown. Abandoning our futile efforts to scale the barricade, we tentatively advance into the forest that adjoins the barrier, crossing a small brook as we do so. Trampling through thickets of brambles, we begin to move among cracked columns and ornate stonework, relics that litter the narrow path that we have made our way on to.

Finally, something glinting silver peers out through the enveloping jungle. Another fence. Squeezing ourselves through the slender gap in the railings, we emerge into a dank, squalid space, which is vaguely recognisable as the ruined Convent of Saint Peter’s Seminary.

Taking a short interlude to catch our breath, we peer out into the mist as the hulking skeleton of the Seminary looms over us. The influences of Corbusier’s Sainte Marie de La Tourette are all too apparent.

Clambering down the inside of the Convent walls, the stains of graffiti are ubiquitous. One sinisterly proclaims, ‘Your soul is mine’. Moving through the rubble, we find ourselves standing in the central courtyard, now completely overgrown. The jungle is promiscuous both inside and outside the Seminary grounds. The dilapidated main building appears clearer now, giving lucidity to its unsightly blemishes and deformities.

We ascend a beautiful curving staircase and are suddenly standing inside a vast chamber, broken open on all sides.

Descending the elegant angled steps, we pass through yet another disfigured fence. The building clearly has problems with the inward leakage of both rainwater and unwanted visitors.

The wind howls through the carcass of Saint Peter’s, rain beginning to speckle the column exteriors.

The crumbling interior arches draw one’s focus to a maelstrom of metalwork and fencing at the end of the space. As we approach the sanctuary, it becomes clear that the framework is obscuring the fragmented altar from sight.

Standing in the sanctuary, there is an ethereal sense of being. The original space’s delicate treatment of light has been condemned, its roof burned away to the timbers by arsonists – galvanized architectural purists, perhaps??

We scramble down the crypt ramp, avoiding the stanchions that support the last few roof joists. I highly doubt that the priests-in-training who inhabited the original Saint Peter’s ever descended in such a calamitous manner.

Entering the sunken crypt, even more homages to Corbusier appear, this time to his Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp.

The spectral light that streams through his windows puddles upon the opposite wall, revealing yet more sprawling works of graffiti. The puddles of water, however, reveal only the detritus accumulated through years of neglect.

Leaving the crypt behind, relieved to have withdrawn from the dark abyss beneath. we fumble along pitch-black passageways that eventually lead us back to the main space.

Ascending the external stairway at the far end of the Seminary, the inverted-ziggurat section of the space becomes apparent, the intimacy of the spaces enhanced from the vast expanses below.

We amble along the decaying walkways that form the perimeter of each of the Seminary’s three upper floors, punctuated the whole way along by the former students’ rooms. With trepidation, we test the strength of the rotting interior arches by crawling across them towards the inner space.

Returning to the external walkway and ascending another floor, we move towards the opposite end of the main building to investigate the burnt-out sanctuary roof. Our investigation rewards us with a fascinating aerial view of the fractured altar, revealing the cruciform support below.

Looking back through the Seminary, the volume is now more enclosed, its moss-covered concrete beams giving a defined sense of form to the space.

The delicate lightness of the concrete beams is amplified in parts where the arches have decomposed, allowing the slender forms of the beams to come to the fore.

The decay within the building is to such an extent that one can see through the concrete skeleton to the ground floor in places.

Pausing for a moment, we then return to a sturdy looking tiled chamber in order to make our final ascent.

3.

Saint Peter’s Seminary: critical arguments

Five chapters

1. Spectres of Spirit: A Deconstruction of the Genius Loci

In his book titled Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, the Norwegian architectural theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz proposes the theory of the ‘Genius Loci’, a notion which has consistently attracted critical attention since it was first devised.[1] Norberg-Schulz identifies the Genius Loci to be an ancient Roman concept and that through etymology it can be traced to mean ‘Spirit of Place’ in the modern English language.[2] The Genius Loci of Roman times was a widely held belief that each autonomous being had its own spirit, often represented in the form of a deity.

It was supposed that it was this spirit that brought about the existence of certain people or places, even determining their very essence.[3] Norberg-Schulz claims that the Genius Loci has remained a core aspect of existence throughout our history, and that although the term is no longer a part of our active vocabulary, the concept remains just as important. He references how artists and writers capture this Spirit of Place, often finding inspiration in the true essence of local character.[4] Norberg-Schulz grounds his concept in Heidegger’s notion of ‘Dwelling’, and the dual aspects of ‘space’ and ‘character’ (the character of an environment) which form the totality of the Genius Loci. These two aspects are responsible respectively for the orientation and identification of man, in an environment which is constituted by ‘things’ which all have inherent ‘meaning’.[5] For Norberg-Schulz, place is understood to be the concrete manifestation of man’s dwelling, the physical matter of which gives rise to the total phenomenon that is the Genius Loci.[6] He asserts the Genius Loci as a singular essence of place that is vital to Holderlin’s pronouncement that it is through poetry that man Dwells on earth.[7] Norberg-Schulz argues that in order for us to do so, we must bring this essence to visibility through architecture, imploring that we ‘concretize the Genius Loci.’[8]

He supports his argument throughout with images of various places which can be determined to bring visibility to the Genius Loci to varying degrees due to their ability to give orientation and identification to man. The use of images is vital in order to prove the instantaneous wholeness of the Genius Loci, that it is possible for one to grasp its entirety much like one would perceive an image in its entirety.[9]

The specific example of Saint Peter’s Seminary provides an intriguing case study for the application of Norberg-Schulz’s theory. As a highly articulated space for religious practice its design sought to communicate the essence of those rituals and the meaning inherent to them, an essence one could equate to the Genius Loci.[10] As a building with a very specific singular purpose – the worship of God – one could reason that the building plausibly had a strong Genius Loci. Visibly enhanced by the daily rituals, religious imagery and architectural language, it would have been clear to visitors what the function of the building was.[11] Photos from the Seminary’s functioning years portray a space of distinct qualities which arguably portray an essence of the space (Fig. 1).[12] However, it is in the use of images that we encounter the first phantom of Norberg-Schulz’s ideology. The architectural historian Alberto Perez-Gomez retaliates that to perceive any cultural milieu in such a two-dimensional, material, and inanimate way is extremely reductive to an argument that seeks humans to Dwell poetically. He claims that such deep-rooted issues as the ones that Norberg-Schulz seeks to relate to architecture and place are deserving of an equally deep portrayal, and not one that is inherently superficial.[13] The use of the image as a medium to correspond the depth of meaning inherent to a place is surely contradictory and falls short of truly orientating and identifying man within his place. Regardless of the meaning that is inherent within the place pictured by the image, such a depiction will always be a shadow of itself.

The use of images is arguably counter-productive, leading to an understanding of architectures role in giving meaning to a place that is based more on aesthetics than anything else. In observing the image of Saint Peter’s shown above, we may perceive some aesthetic signifiers of narrative, such as the priest walking down the ramp towards the crypt. This identifies the space as being used for religious purposes, and that there is a form of ritual inherent to the usage of the space. But we have little idea of the wider context of the situation pictured, whether the priest carried this out every day for example, or whether he did indeed truly believe in the cause for which his vocation existed. These signifiers are ambiguous, and only communicate a faint trace of the place’s spirit. Problems also arise in his inability throughout his book to portray a place that is deficient in a sense of the Genius Loci, making little effort to elucidate the antitheses of his theory.[14]

The issues that arise when Norberg-Schulz’s use of imagery is interrogated are symptomatic of wider problems that permeate his theory in general. Another aspect of the theory of the Genius Loci that is troubling is the potential for subjective differences in such a phenomenon. In the specific case of Saint Peter’s, this weakness of the Genius Loci is exemplified in the difference between the subjective experiences of a religious and non-religious person when visiting the Seminary when it was functional.[15] For a religious person, the space may have held an essence that was steeped in its denomination as a space for religious practice (in fact, even as a ruin it may still give rise to this feeling[16]).

However, for a non-religious person the space would undoubtedly have had qualities of orientation and identification that differ, thus leading to a different Genius Loci and contradicting its totalising nature. The architectural historian Harriet Edquist questions how the Genius Loci, if it does indeed exist, manifests itself. For Norberg-Schulz, she claims, it appears to manifest itself directly to the human consciousness.[17] This implies a universality to the spirit of a certain place, that it is the same objective essence irrelevant of the subject who experiences it. For Edquist, this is a key flaw in the ideology of the Genius Loci, a flaw which suggests ‘the obliteration of the human subject’.[18] It is clear that Norberg-Schulz avoids mention of the human subject in his theory, instead grounding his work in Heidegger’s notion of ‘Dasein’, or ‘being in the world’.[19] This notion emphasises a oneness between subject and object, but fails to provide for any form of differentiation between the Dasein of one person to another. His theory imposes a meta-narrative that is supposedly universal, which conditions everyone to experience a space in the same way.[20]

In the same way that it concretises the subjective perception of the spirit of a certain place into one definite essence, the theory attempts to concretise narrative into the Genius Loci.[21] In asserting a totality of spirit, the theory implies the compression of layers of history into a singular essence, which denies the importance, or even presence, of time. In presenting his theory, Norberg-Schulz uses a series of examples of places which exhibit a certain Genius Loci, the majority of them being bygone architectures of communities that were rooted in their time and place.[22] By denying time an active role in the conception of Genius Loci, he creates a conflict: the Genius Loci must be able to evolve as time progresses if it is to be seen to be as anything more than a transient phenomenon, or it must be a static, unchanging thing that persists despite changes to the objective physical realm that it is manifested from. Norberg-Schulz seems to opt for the latter, a choice which has led to critics accusing him of being strongly traditional and nostalgic.[23] Using a lexicon of terms such as ‘concretise’, it can indeed appear that he desires to fossilise the process of time.

Again, Saint Peter’s provides strong evidence to counter Norberg-Schulz’s theory, by virtue of its clear aura of multiple narratives that continue into the present day.[24] This narrative fragmented from the singular into the plural at the point when the Seminary was deconsecrated and abandoned, its purpose laid to indeterminacy. This indeterminacy resulted in the contestation of the space by various usages, and the conflict over its purpose by numerous opinions.[25] This pluralistic existence contradicts the theory of Genius Loci that is based on a space having a singular, total essence, and yet the space continues to evoke meaning for many of those who visit it, finding it to have a certain spirit.[26]

In recent years various organisations have attempted to find new purpose for the decaying shell of Saint Peter’s, invariably failing in their attempts to do so. What each of these attempts to bring determinacy and purpose back to the Seminary could be seen as is an attempt to resuscitate the Genius Loci of the space. There is an evident drive amongst some, many from the architectural profession, that something must be done to return a purpose to Saint Peter’s.[27] The notion that the building must serve a purpose, that it must retain a singular essence, is one that haunts it and leads to the contention that the theory of the Genius Loci is a spectre of the Seminary. As the French philosopher Jacques Derrida points out, spectres occupy the past and the future, if not actually the present. They are, for him, a future possibility.[28]

The statement that architecture must ‘concretise the genius loci’ is one that must ring with familiarity for those who propose the revitalisation of Saint Peter’s, if not faintly ironic due to the dilapidated state of its concrete vaults. What can be said of the Genius Loci at the Seminary in its current state then, is that it is not present as a whole, but fragmented and transitory. The building’s essence, if such a thing does exist, is constantly in flux – there is no ‘stabilitas loci’, to borrow the words of Norberg-Schulz.[29]

Christian Norberg-Schulz’s ideology relating to the Genius Loci is one that is fraught with flaws, such as its lack of engagement with subjectivity, and its relationship to narrative of place. The theory emphasises the singular totality of spirit of place, and yet its existence has been haunted by its failure to engage with plurality. Its insistence on an essentialist homogenous entity that unites all difference has resulted in the haunting of its very own spirit by spectres.

[1] Rowan Wilken, ‘Critical Reception of Norberg-Schulz’s Writings on Heidegger and Place,’ in Architectural Theory Review 18, no. 3 (2013), 341.

[2] Christian Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1980), 18.

[3] Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci, 18.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 19.

[6] Wilken, ‘Critical Reception,’ 343.

[7] Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci, 23.

[8] Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci, 23.

[9] Alberto Perez-Gomez, ‘The City is not a Post-Card,’ in An Eye for Place: Christian Norberg-Schulz: Architect, Historian and Editor, ed. Gro Lauvland (Oslo: Arkitektur Publisering, 2009), 28.

[10] Karen Wenell, ‘St Peter’s College and the Desacralisation of Space,’ in Literature and Theology 21, no. 3 (Autumn 2007), 263.

[11] Wenell, ‘St Peter’s College and the Desacralisation of Space,’ 262.

[12] Gillespie, Kidd & Coia Archive, ‘Sanctuary Ramp,’ Glasgow School of Art,

Link no longer active – gsaarchives.net/catalogue/index.php/informationobject/browse?places=20848&collection=20333&sort=lastUpdated&view=card&showAdvanced=0&sq0=Architecture&sf0=subject&onlyMedia=1&topLod=0&rangeType=inclusive

[13] Perez-Gomez, ‘The City is not a Post-Card,’ 30.

[14] Wilken, ‘Critical Reception,’ 346.

[15] Erik Champion, ‘Norberg-Schulz: Culture, Presence and a Sense of Virtual Place,’ in The Phenomenology of Real and Virtual Places, ed. Erik Champion (London: Routledge, 2018), 218.

[16] Refer to survey

[17] Harriet Edquist, ‘Genius Loci,’ in Transition 4, no. 1 (Spring 1988), 81.

[18] Edquist, ‘Genius Loci,’ 81.

[19] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1978), 106.

[20] Champion, ‘Norberg-Schulz: Culture, Presence and a Sense of Virtual Place,’ 224.

[21] Perez-Gomez, ‘The City is not a Post-Card,’ 31.

[22] Gunila Jiven and Peter J. Larkham, ‘Sense of Place, Authenticity and Character: A Commentary,’ in Journal of Urban Design 8, no. 1 (2003), 68.

[23] Massimo Cacciari, Architecture and Nihilism on the Philosophy of Modern Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 108.

[24] Richard Waite, ‘Renewed hope for Cardross seminary after church finds new owner,’ in Architects Journal, July 27, 2020, https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/renewed-hope-for-cardross-seminary-after-church-finds-new-owner

[25] Diane Watters, St Peter’s, Cardross: Birth, Death and Renewal (Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland, 2016), 188.

[26] Refer to survey

[27] NVA, ‘Debate of the future of St Peters Seminary at the Venice Architectural Biennale 2010,’ July 30, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LDuiqcRnMXM

[28] Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International (Routledge: London, 2006), 9.

[29] Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci, 19.

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 1

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 2

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 3

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 4

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Part 5

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Conclusion

Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Dissertation by Third Year Student at Edinburgh School of Architecture information / images from Daniel Lomholt-Welch

Edinburgh School of Architecture Student Projects

e-architect are following the progress of architecture student Daniel Lomholt-Welch during his degree studies at Edinburgh University.

Year 2, Semester 2: Valencia Community Library building design

Second Year Student Projects at Edinburgh School of Architecture

First Year Student Projects at Edinburgh School of Architecture

image courtesy of D L-W

First Year Student Projects at Edinburgh School of Architecture

Education Building Designs

New Macallan Distillery in Speyside

Design: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP)

photo © Simon PricePA Wire

Architecture and Landscape Architecture | Edinburgh College of Art

Comments / photos for the Saint Peter’s Seminary Cardross Study Introduction page welcome