The Kunstmuseum, Basel Building, Swiss Design, Architect, Images, Amerbach Cabinet Project

The Kunstmuseum in Basel

Öffentliche Kunstsammlung: Art Gallery Building in Switzerland – design by Christ & Gantenbein, architects

2 Feb 2016

The Kunstmuseum in Basel

Location: Basel, Switzerland

Design: Christ & Gantenbein

Extended Kunstmuseum Basel opens mid April

The Kunstmuseum Basel ranks among the most renowned institutions of its kind in Europe and beyond. Its world-famous collection, the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, now encompasses around 4.000 paintings, sculptures, installations, and videos as well as 300.000 drawings and prints from seven centuries. Its historic nucleus is the Amerbach Cabinet, the art collection built by Basilius Amerbach, a prominent citizen of Basel. It was purchased by the city and the university in 1661 and displayed to the public starting in 1671, arguably making it the world’s oldest municipal art collection.

The enlarged Kunstmuseum Basel (left: new building, right: main building). Photo Julian Salinas. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

The Kunstmuseum Basel’s treasures include some of the finest art of the Renaissance in the Upper Rhine Valley such as the world’s largest collection of works by the Holbein family as well as masterpieces by Konrad Witz, Martin Schongauer, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Matthias Grünewald, and others. Another highlight is nineteenth-century art, where the museum has sizable ensemble of paintings by Arnold Böcklin and Ferdinand Holder as well as outstanding works by Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Vincent van Gogh. The museum’s division of twentieth-century art focuses on Cubism (Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger), German Expressionism (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka), Abstract Expressionism (Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, Franz Kline) and American art after 1960 (Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, Donald Judd, Cy Twombly). Important ensembles of works from recent decades by artists including Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, On Kawara, Louise Lawler, Simon Starling, Olafur Eliasson, Rosemarie Trockel, Pierre Huyghe, and Gabriel Orozco round out the collection.

Kunstmuseum Basel | Gegenwart. Photo Julian Salinas. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

Over the centuries, the steady growth of the collection and the desire to present it in keeping with evolving standards necessitated several relocations within Basel. Finally, in 1936, the museum’s treasures found a permanent home in the present-day main building on St. Alban-Graben. The first major enlargement came in 1980, when the Museum für Gegenwartskunst—one of the world’s first dedicated museums of contemporary art, it is now known as Kunstmuseum Basel | Gegenwart—opened its doors on St. Alban-Rheinweg.

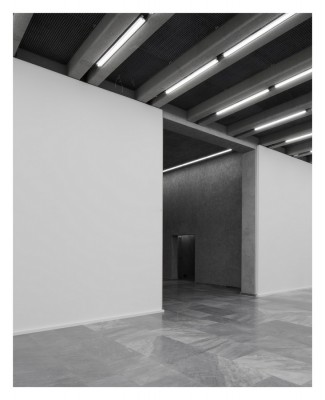

Kunstmuseum Basel | new building. Photo Walter Mai. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

Most recently, we have added a third venue: a new building has risen across the street from the main building, to which it is connected by an underground passageway. It accommodates special exhibitions as well as presentations of art from the collections. Designed by the Basel-based architecture firm Christ & Gantenbein, the new building is also a fresh highlight in the city’s architectural landscape. With the inauguration of the new building and the reopening of the refurbished main building in mid-April 2016, the Kunstmuseum Basel now has three venues for the presentation of its treasures.

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1969. Kunstmuseum Basel – Ankauf 1975. Photo Stefano Graziani. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

The Interaction of Art and Architecture

On the Content of the New Building

Text: Bernhard Mendes Bürgi

Conceptual Fundamentals

What makes the Kunstmuseum Basel so unique—its salient characteristic, as it were—is the extraordinary breadth of its collection, which, with works of the very highest quality, spans the period from the fifteenth century to the present day, and is continuously updated. Assembling seven centuries of (Western) art history under one roof is no mean feat, especially as many of the great collections of old masters—that of the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid and the Musée du Louvre in Paris, for example—remain relatively static, having added little that postdates the end of the nineteenth century. And while The Museum of Modern Art in New York has indeed become a benchmark for modern and contemporary art, it does not have the echoing chamber of a collection of Old Masters, as the Kunstmuseum Basel does.

Kunstmuseum Basel | new building. Photo Stefano Graziani. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

A steadily growing collection and ever more exacting demands with regard to how works of art are presented have repeatedly necessitated new architectural departures. The Kunstmuseum’s main building on St. Alban-Graben designed by Christ & Bonatz in 1936 was therefore modernized in parallel to work on the new building. Earlier efforts to enlarge our architectural infrastructure culminated in the erection in 1980 of one of the world’s first museums of contemporary art on St. Alban-Rheinweg, an annex that was likewise renovated in 2005. Since the acquisition of the adjoining Laurenz Building, moreover, premises formerly occupied by the Swiss National Bank, it has been able to house not only its library and offices there, but also the University of Basel’s Art History Department. There were net gains in exhibition space in the main building too, and room enough for the installation of a bookstore / museum shop and bistro.

Kunstmuseum Basel | new building. Photo Stefano Graziani. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

Recent years have seen not only a steady stream of acquisitions, especially of contemporary art, but also an intensification of our exhibition activities with major shows of Hans Holbein the Younger, Pablo Picasso, and, most recently, Charles Ray—to name but a few. Each of these exhibitions grew out of a different part of the collection (contemporary art, Modernism, and Old Masters) and each set out to investigate or revisit important aspects of the collection. As there were no plans to hold major exhibitions at the Kunstmuseum initially, the 1936 Christ & Bonatz building was not furnished with the necessary wherewithal in terms of

infrastructure. Curators were therefore obliged to improvise, which they did by temporarily repurposing the galleries earmarked for the permanent collection.

Kunstmuseum Basel | new building. Photo Stefano Graziani. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

Not only did this necessitate many ad hoc rehangings, but it also had the effect of decimating the second-floor galleries and gravely impairing the unparalleled tour of Modernism that they might otherwise offer. Thus it really was our commitment to special exhibitions, coupled with our anxiety to spare the galleries reserved

for the collection the upheavals that such shows are wont to cause, that triggered the search for a suitable premises close to the existing museum in which to install a dedicated exhibition infrastructure.

Villa Malaparte, Günther Förg, 1983/2005. Gift from the artist 2005. Photo Stefano Graziani. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel

Above and beyond this, we wanted the new building to provide more space for an ever larger collection, especially for the works of the 1950s and later, such as those by Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, and Donald Judd. This in turn would free up space in the main building for a collection ranging from Konrad Witz and Hans Holbein the Younger to Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti, while the Museum für Gegenwartskunst (now the Kunstmuseum Basel | Gegenwart) would be able to focus exclusively on art from the 1990s to the present.

Kunstmuseum Basel | new building. Photo Stefano Graziani. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

The creation of additional in situ storage space, first and foremost a specially air-conditioned area to be set aside for the photography collection that has grown considerably in recent years, was also high up on our wish list. From the logistical point of view, the closure of our satellite storage premises promised advantages that museums in big cities, which find themselves having to move their vaults further and further out of town, cannot usually enjoy. The Louvre’s choice of Liévin near Lens for conservation and storage is but one example among many. Also essential was a loading bay for the delivery and dispatch of works of art in compliance with international standards, which in concrete terms meant a secure, air-conditioned drive-in loading bay with direct access to a cargo elevator.

The other factors included visitor-friendly ticketing and cloakroom services and multipurpose event spaces. A large foyer with room for up to a thousand people that could be used for openings, symposia, performances, concerts, and lectures was considered especially desirable. Nor should space for the museum’s

educational and outreach activities be forgotten.

If at all possible, the new building was to be situated in the immediate vicinity of the main building, thus becoming an integral, and indeed assertive, part of its specific urban context. The idea was that it should enter into a dialogue with the main building; not to outshine it, but to enhance and empower it.

The main stipulations of the concept, therefore, were that the galleries be centrally located, that the architecture in the exhibition areas support rather than dominate the art, and that the main and the new buildings be physically connected. The overriding aim was to upgrade the infrastructure of the Kunstmuseum Basel as custodian of a world-famous collection, and to strike a balance between our collecting and exhibiting activities. The new building was also to become an architectural landmark, symbolizing an innovative new departure both for Basel as a city and for museums worldwide.

The Realization

Once the Burghof site had been purchased, we were able to invite entries to an anonymous competition for the building to be erected there. The design selected was that submitted by Christ & Gantenbein, a comparatively young architects’ office from Basel, which is perhaps surprising given the many famous names that took part.

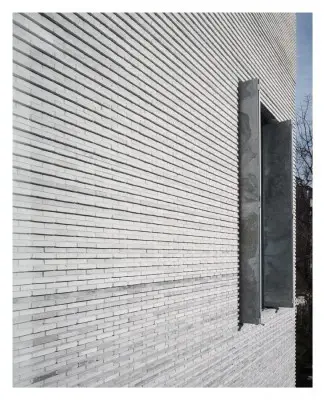

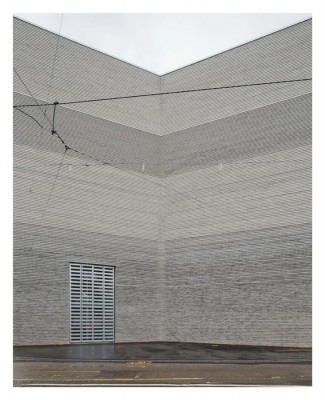

The winning project submitted in the second stage of the selection process already bore all the distinctive hallmarks that were to be developed as planning progressed, above all the concave “kink” that references a historical group of houses, and lends an exterior presence that might otherwise seem monolithic, a wonderful, almost playful, lightness of touch. Then there is the LED frieze combining state-of-the-art IT with a traditional neoclassical frieze like the one that adornes the facade of the museum of 1849 by Melchior Berry on Augustinergasse, which for a long time housed the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung. Even the underpass connecting the two buildings beneath Dufourstrasse and lit with daylight from the courtyard at the rear was likewise an integral part of Christ & Gantenbein’s plans right from the start.

As the planning work progressed, this underground passage on the first lower level acquired an ever sharper profile as a generously dimensioned access area far removed from conventional notions of tunnels as dark and narrow conduits.

Thus it encompasses both a large foyer and, thanks to the daylight supplied by the aforementioned courtyard, the first of the exhibition spaces. Following the conceptual logic of the design, these are spread over all four of the floors that are open to the public, and actually monopolize the whole of the first and second floors.

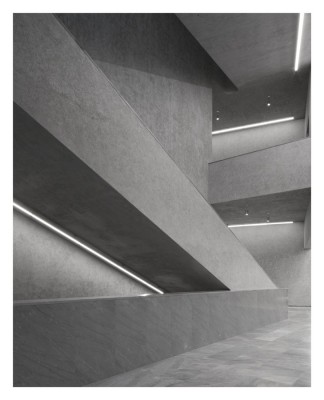

Despite featuring works by Frank Stella, among others, the foyer does not actually constitute an exhibition space as such. It is more an event space accentuated by works of art, which for a change of emphasis can be rehung from time to time. The underpass allows visitors to move freely between the main building and the extension, which can also be reached directly from the street via its own ground-floor entrance area. All the public access areas have the same matt gray marble flooring, which looks especially impressive in the monumental stairwell.

The stairwell, incidentally, is an exceptionally good example of Christ & Gantenbein’s inspired engagement with the main building, as evidenced by their use of rough scraped plaster for parts of the walls and ceilings, and by the round skylight crowning the almost sculptural-looking staircase. The staircase provides access to the second floor which, furnished with skylights, is to be used mainly for special exhibitions. That these would draw on works from all parts of the collection was a point the architects should be reminded of, I felt. They should certainly not imagine that the only works that would ever hang there would be Modernist or later—works for which the proverbial white cube counts as the ideal space. Their job was rather to create a space that would make just as good a backdrop for the art of the Renaissance and of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

The first-floor equivalent of the skylights that were a conditio sine qua non of the second floor are the tall windows built into the side walls which, besides flooding the galleries with light, also permit wonderful views across the city and lend vivid immediacy to the architectural presence of the main building across the street. The linear LED lighting is built into the concrete ribs in the ceiling, which, besides making for structural clarity, also accommodate the HVAC ducts.

All the galleries are perfectly proportioned in terms of length, breadth, and ceiling height—this being just as essential to the effective staging of art as the harmonious interaction of floor, ceiling, and wall. Both the architects and the museum attached the utmost importance to the physical, sensuous presence of the materials used for every detail, no matter how tiny, and discussed these at great length—whether or not there should be baseboards, for example, how the doorways between galleries should be articulated, what the metal fire doors and window shutters should look like. Even the thick layer of plaster coating the walls was chosen not just to facilitate the installation of the artworks, but also as an expression of our conviction that only in an exhibition architecture made of carefully selected materials can art truly flourish. The choice of industrial parquet flooring in the galleries deserves a special mention here. Once widely used, it has become quite rare in recent years, although its sensational reinterpretation at the hands of Christ & Gantenbein makes it once again contemporary. The quality materials on the inside are matched by the brick facades on the outside, which from ground up pass through a several subtle gradations of gray.

The enlarged Kunstmuseum Basel (left: new building; right: main building). Photo Julian Salinas. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel.

To be able to achieve such physical presence and architectural rigor, one decision was clear right from the start: specifically, to dispense with the muchvaunted system of flexible room dividers so often used by many new museums, among them Renzo Piano’s Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Insisting on definiteive walls rather than non-committal partitions requires great courage on the part of both museum and architects. But here, too, unité de doctrine prevailed—the doctrine being our shared determination to eschew the kind of faceless, nondescript, protean interiors that are currently en vogue. Besides, what makes the new building’s exhibition spaces so attractive is the fact that they can be used with absolute flexibility. Nor are there any permanent installations in the pipeline that might stand in the way of a potential “reinvention” of the new building. The need to obtain orthogonal exhibition spaces from an irregularly shaped plot, which being relatively small had to be exploited to the full, was likewise an important factor informing the architects’ design. Thus the galleries vary in size and in some cases are larger than those in the main building. Being arranged in sequences, moreover, they will allow us to create coherent exhibition organisms, which in their turn will function as germ cells for the vitality and radiance of the institution as a whole.

Excerpt from Kunstmuseum Basel, New Building, edited by Kunstmuseum Basel, Bernhard Mendes Bürgi, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, 2016. The book will be published in April.

The Kunstmuseum in Basel images / information received 020316

Location:Basel, Switzerland ‘

Swiss Architecture

Basel Architecture

Design: various architects – photos

photo : the antillia collective

Swiss Architecture Designs – chronological list

Basel Buildings

Novartis HQ

Design: various architects – photos

photo : Novartis

Novartis HQ Basel

Roche Tower

Herzog & de Meuron

image courtesy of architects

Roche Tower Basel

Ozeaneum – Oceanographic Museum, Germany

Behnisch Architekten

photo : Roland Halbe

Comments / photos for the The Kunstmuseum in Basel page welcome

The Kunstmuseum in Basel Building – page

Website: Christ & Gantenbein