Endangered buildings designed by black architects awarded Getty funding, Modernist architecture

Endangered buildings designed by black architects awarded Getty funding

July 18, 2024

Eight Endangered Buildings Designed by Black Architects Awarded Getty Funding

In partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the grants will support conservation planning, training, and storytelling for modern sites

Azurest South, designed by Amaza Lee Meredith and built in 1934. Virginia State University, St. Petersburg, VA. Photo: Hannah Price

Eight Endangered Buildings Designed by Black Architects Awarded Getty Funding

LOS ANGELES — The Getty Foundation and the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund announced today eight buildings will receive crucial funding from the Conserving Black Modernism initiative, a $3.1 million grant program to preserve historic modern architecture by Black architects and designers.

From a dormitory in Mississippi designed by one of the 20th century’s most influential Black architects, to a theater in Washington D.C. named after the first Black actor to play leading roles in Shakespeare plays, the grants affirm the importance of African American architects to the history of modernism by preserving their work. Getty funding will support conservation planning and emergency repairs, expand the skills of the people who care for these buildings, and promote broader public understanding of trailblazing Black professionals who contributed to the modern movement.

“With Conserving Black Modernism, we’ve taken actionable steps to save endangered sites that represent African American activism, creativity, and resilience,” says Joan Weinstein, director of the Getty Foundation. “Our partnership with the National Trust has been critical to supporting cultural heritage that embodies Black excellence in modern architecture.”

Established in 2022, Conserving Black Modernism is the Getty-funded portion of a partnership program with African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, the largest preservation campaign to support the longevity of African American sites. The Action Fund today also announced funding for a total of 30 sites representing Black history across the U.S., which includes the eight sites supported by Getty funding.

“Through this year’s grant announcement, we are thrilled to support eight historic sites celebrating Black Modernism – an architectural style that deserves to be recognized and celebrated,” says Brent Leggs, executive director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund. “As a nation, we must recognize and honor the profound contributions of these Black architects and designers, whose works serve as community landmarks, sources of cultural pride, and often, symbols of justice and equity. We are excited to partner with Getty for the second year of the Conserving Black Modernism program, and we look forward to ensuring that these sites and their stories continue to inspire future generations.”

African American architects and designers played influential roles in the development of modernism in the United States, yet their contributions have been largely overlooked. While a handful of Black architects and designers gained notoriety, most worked in the shadow of larger offices under white architects of record, and thus remain relatively unknown. Getty created the Conserving Black Modernism initiative to address this oversight and help write a more complete story of the modern movement.

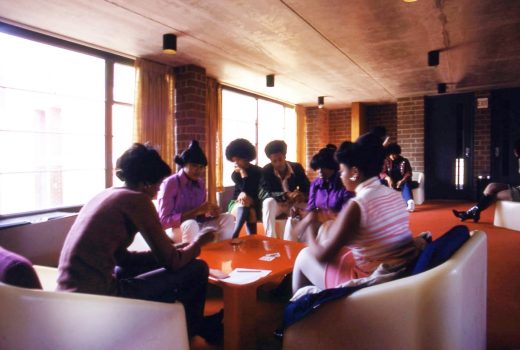

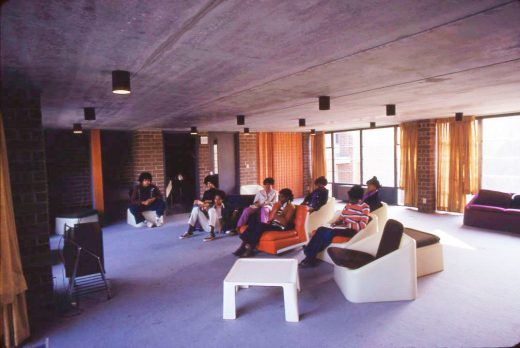

Interior of Kenneth G. Neigh Dormitory Complex, designed by J. Max Bond and built in 1970. Mary Holmes Community College, West Point, MS. Courtesy of Davis Brody Bond, a Page company

Conserving Black Modernism Grantees for 2024

Azurest South, designed by Amaza Lee Meredith and built in 1934

Virginia State University, St. Petersburg, VA

photo : Hannah Price

Azurest South in Petersburg, VA — Completed in 1934, Azurest South is the home and studio designed by the pioneering African American architect Amaza Lee Meredith. Located on the Virginia State University campus, where she established the Fine Arts program and lived with her partner Dr. Edna Meade Colson, the home is a colorful example of the International Style. Funding will support the implementation of a conservation management plan for the building.

Dansby, Brawley, and Wheeler Halls at Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA — Leon Allain, a prominent African American architect in the Atlanta area, designed Dansby, Brawley, and Wheeler halls at Morehouse College through the early 1970s. Funding will support building assessments and an Historic Structures Report for the three halls.

Ira Aldridge Theater, designed by Hilyard Robinson and Paul R. Williams and built in 1961

Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts at Howard University, Washington, D.C.

photo : Julie and Barry Harley of Visual 14

photo : Julie and Barry Harley of Visual 14

Ira Aldridge Theater, Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts at Howard University, Washington, D.C. — The Ira Aldridge Theater was named for a famed 19th century African American actor, best known for his performances of Shakespeare. Designed by Hilyard Robinson and Paul R. Williams, the theater was completed in 1961 as part of Howard University’s campus. Funding will support an Historic Structures Report and an interpretation plan.

JFK Recreation Center, designed by Robert T. Coles and built in 1963

Buffalo, NY

photo : Jalen Wright

John F. Kennedy Community Center, Buffalo, NY —The JFK Recreation Center was designed by Robert T. Coles as his thesis project at MIT and completed in 1963. The building currently hosts a range of nonprofits and community activities. Funding will support a comprehensive preservation plan.

Kenneth G. Neigh Dormitory Complex, designed by J. Max Bond and built in 1970

Mary Holmes Community College, West Point, MS

photo Courtesy of Davis Brody Bond, a Page company

Interior of Kenneth G. Neigh Dormitory Complex, designed by J. Max Bond and built in 1970

Mary Holmes Community College, West Point, MS

photo Courtesy of Davis Brody Bond, a Page company

Kenneth G. Neigh Dormitory Complex, West Point, MS — Designed by J. Max Bond Jr. and completed in 1970, the Kenneth G. Neigh Dormitory Complex is currently in an advanced state of deterioration as Mary Holmes Community College has been closed since 2005. Funding will support an adaptive reuse feasibility study for the complex.

Masjid Muhammad, Nations Mosque, designed by David R. Byrd and built in 1960

Washington D.C.

photo : E.A. Crunden

Masjid Muhammad, Nations Mosque, Washington, D.C. — Completed in 1960, Masjid Mohammad, Nations Mosque was designed by David R. Byrd. The building represents one of the oldest Black Muslim congregations in the United States. Funding will support engineering and environmental studies for the building’s planned expansion, in addition to limited capital improvements.

Robert T. Coles House, designed by Robert T. Coles and built in 1961

Buffalo, NY

Robert T. Coles House, Buffalo, NY — Robert T. Coles, the first African American Chancellor of the American Institute of Architects, designed and built his House and Studio in 1961. The two-story building is composed of prefabricated units set back in a garden and courtyard. Funding will support a Historic Structures Report, conservation plan, and a reuse and feasibility study.

Universal Life Insurance Co. Building, Memphis, TN — Designed in 1947 by McKissack and McKissack, one of the oldest Black-owned architectural firms in the United States, the Universal Life Insurance Company Building was completed in 1949. Funding will support a cultural interpretation plan and critical repairs to certain sections of the building.

Ira Aldridge Theater, designed by Hilyard Robinson and Paul R. Williams and built in 1961. Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts at Howard University, Washington, D.C. Photo: Julie and Barry Harley of Visual 14

The first round of eight grantees for Conserving Black Modernism in 2022 included an award-winning swimming pool and pool house in Wichita, Kansas, a vibrant cultural center in Watts, California, and some of the oldest Black Baptist churches in the country. This second round of grants adds the first building designed by a woman, Amaza Lee Meredith, who was never granted licensure as a registered architect but nevertheless completed important designs throughout Virginia and New York. See here for all Conserving Black Modernism grants awarded since 2022.

Conserving Black Modernism is an extension of the Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern initiative, which awarded 77 grants totaling $11.8 million between 2014 and 2020 that supported conservation planning and research for modern buildings and sites from around the world.

The Getty Foundation’s grant program is one of several efforts by Getty to broaden awareness of and preserve Black architectural heritage, including the Getty Conservation Institute’s African American Historic Places Los Angeles initiative and the Getty Research Institute’s joint acquisition of the archive of Paul R. Williams, one of the best-known 20th-century Black architects in the United States.

The Getty Foundation fulfills the philanthropic mission of the Getty Trust by supporting individuals and institutions committed to advancing the greater understanding and preservation of the visual arts in Los Angeles and throughout the world. Through strategic grant initiatives, the Foundation strengthens art history as a global discipline, promotes the interdisciplinary practice of conservation, increases access to museum and archival collections, and develops current and future leaders in the visual arts. It carries out its work in collaboration with the other Getty Programs to ensure that they individually and collectively achieve maximum effect. Additional information is available at www.getty.edu/foundation.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation protects historic landscapes and buildings representing our country’s diverse cultural experience by taking direct action and inspiring broad public support. Chartered by Congress in 1949 as a privately funded organization and committed to honoring the histories of all Americans, the National Trust collaborates with partners and allies to save places, educate the public, and use preservation to address urgent challenges and serve communities today. Learn more about the National Trust for Historic Preservation at https://savingplaces.org/

In November 2017, the National Trust for Historic Preservation launched its African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund (AACHAF) to make an important and lasting contribution to the American landscape by preserving sites of Black activism, achievement, and resilience. Since 2017, it has raised over $140 million and supported 304 grantees nationwide. Learn more about the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund at www.savingplaces.org/actionfund.

Previously on e-architect:

July 16, 2020

Getty Foundation Keeping it Modern Grants 2020

Getty Foundation Announces Final Round of Keeping It Modern Architecture Conservation Grants

2020 Keeping it Modern Grants from Getty Foundation

Los Angeles – Triangle-studded fairgrounds that commemorate Senegalese independence, shimmering water towers that rise from the Persian Gulf’s desert shores, a British zoo with Soviet modern flair, and a serene Benedictine monastery designed by architecturally trained monks are among 13 significant 20th-century buildings that will receive $2.2 million in Keeping It Modern grants, the Getty Foundation announced.

Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam, Netherlands (architect: Gerrit Rietveld, 1963)

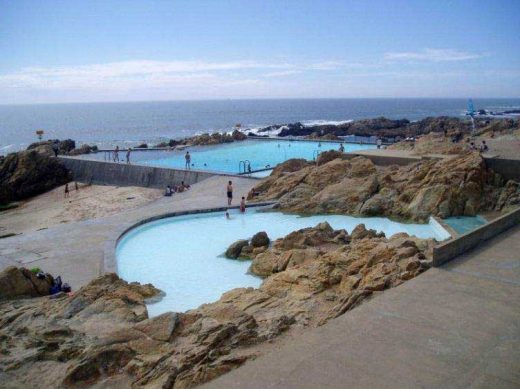

Swimming Pools, Leça, Portugal (architect: Álvaro Siza, 1966)

photo from Alvaro Siza Vieira

Leça Swimming Pools

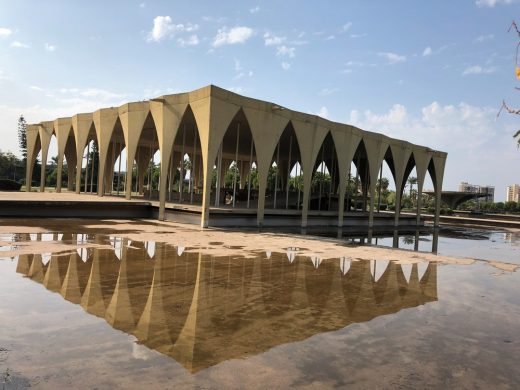

International Fairgrounds, Dakar, Senegal (architects: Jean-François Lamoureux and Jean-Louis Marin, 1974)

Kuwait Towers, Kuwait City, Kuwait (architect: Malene Bjørn, 1976)

photo © Adrian Welch

Kuwait Towers

Getty Foundation Keeping it Modern Grants for 2018

Eleven new grants include first projects in Cuba and Lebanon, as well as the famous Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri

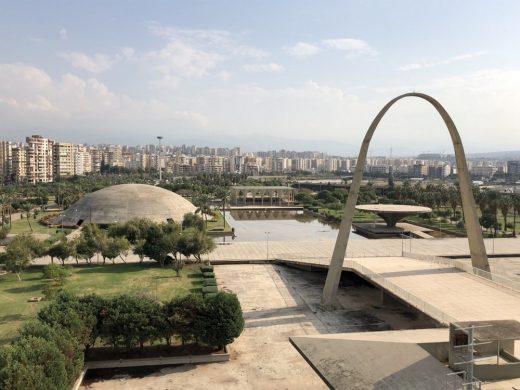

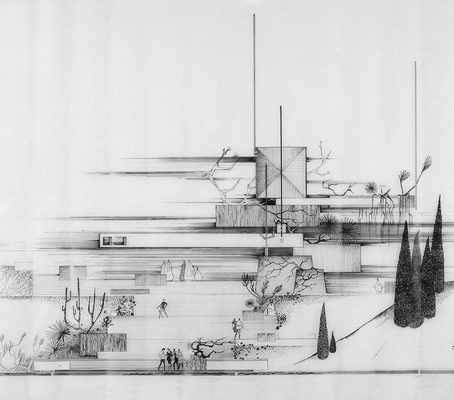

Oscar Niemeyer’s Permanent International Fairground in Tripoli, Lebanon:

photo © UNESCO Beirut Office

Getty Foundation 2018 Keeping it Modern Grants

Oscar Niemeyer’s Museum of Lebanon, Rashid Karami International Fairground Tripoli:

photo © UNESCO Beirut Office

External view of the University of Leicester Engineering Building tower and workshops:

photograph © University of Leicester (photographer Simon Kennedy)

TU Delft Aula building:

photo © Marc Blommaert

Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo, Italy – Aerial view:

photo owned by Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo – Photographer: Paolo Bianchi

Getty Foundation Keeping it Modern Grants

Getty Foundation Keeping it Modern

Deadlines and criteria for the next round of Keeping It Modern applications are available at www.getty.edu/foundation.

Getty Foundation Keeping it Modern Grants for 2017

Bauhaus Building One of Twelve Recipients of Getty Fou3ndation’s Keeping It Modern Grants

photo © Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, photo © Yvonne Tenschert

Getty Foundation Keeping it Modern 2017 Grants

Villa E-1027, Cap Moderne, photograph Manuel Bougot www.manuelbougot.com. 2016

Modern Architecture Conservation Grants 2016 – Keeping It Modern by the Getty Foundation – 2016

Getty Foundation Keeping it Modern Grants for 2017

Location:1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, California 90049-1685

Modern Architecture – Major Modernist Buildings

Post-war Architecture

photo : Morley von Sternberg

Post-war Architecture

These Modern buildings

Boston City Hall, Boston, Massachusetts (architects: Kallmann, McKinnell, & Knowles);

photo © Naquib Hossain/Dotproduct Photography

Boston City Hall Building

Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex, Sidi Harazem, Morocco (architect: Jean-François Zevaco);

Image © Frac Centre-Val de Loire Collection.

Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex Building

Modern English house – one of the first Modern houses in England

Comments / photos for the 2020 Keeping it Modern Grants: Getty Foundation page welcome